By Don Schwennesen | Photographs by Carl Davaz

At first glimpse, the Welcome Creek Wilderness seems undistinguished compared to the grandeur of Montana’s flagship wilderness areas. One Forest Service official calls it Montana’s mundane wilder ness. There are no lakes, no snowy crags, no high cirques, no hanging valleys within its boundaries. Draped down the northeastern slopes of the Sapphire Mountains, Welcome Creek is a relatively small reserve of steep, forested ridges and deep, angular stream courses punctuated by sentinel rock outcrops and low cliffs.

Named for the main watershed that fingers into its upper reaches, this 28,135-acre wilderness provides an enclave of sylvan seclusion amid logging roads and commercial forests that characterize much of the 60-mile-long Sapphire Mountain chain southeast of Missoula. From the spring-fed creek issues pure, cold water that was doubtless welcome enough to the early miners who trekked the surrounding dry summer ridges more than a century ago. The few visitors who find their way up the Welcome Creek canyon today are rewarded with solitude and occasional glimpses of early mining digs, rotting log cabins, and forgotten relics fast disappearing into the undergrowth.

Bounded on the east by Rock Creek, one of the nation’s most celebrated blue-ribbon trout streams, the Welcome Creek Wilderness climbs to the crest of the Sapphire Mountains through timbered country of surprising ruggedness. The heart-shaped wilderness area is scarcely 7 miles wide and 10 miles long, yet it challenges even the experienced wilderness explorer. Innocent-looking spur ridges climb with a severity that will impress the most determined hiker. Sloping gently from the top of the range, the ridges soon fall away toward Rock Creek in breaklands

that give the valley a canyon character even though it is devoid of cliff walls and mantled by forest. From 7,723-foot Welcome Mountain, the highest point in the northern Sapphires, the terrain drops 4,000 feet in less than 5 miles. Hikers climbing Welcome Mountain via the Sawmill Creek trail ascend even faster, climbing 3,000 feet in less than 2.5 miles before gaining the long, luxurious crest of Solomon Ridge.

An important elk summer range, the wilderness also provides undisturbed habitat for pine martens and other wildlife species that require mature forests. Its ridges and canyons are cloaked with a composite of old-growth forests ranging from dry, open Douglas fir slopes to wet spruce bottoms to parklike ridge tops where small, succulent huckleberries flourish under a cool canopy of lodgepole pine. The lower reaches of Welcome Creek support a good fishery of pan-sized cutthroat and other trout. The small creek is almost forgotten next to Rock Creek, with its rich, challenging fishery of rainbow, brook, cutthroat, brown, and Dolly Varden trout, but Welcome Creek provides spawning and rearing areas important to the larger stream.

Welcome Creek was added to the national wilderness system in 1977 after a short, relatively uncontested campaign in which congressio nal attention focused on more controversial areas where the timber industry sought harvesting rights. Many wondered, before and after, why such an area should be added to a national wilderness system that includes some of the grandest and most scenic of America’s public lands. To others who have wandered the Sapphires, with their long, graceful ridges and lodgepole pine parks, the answer is clear.

“Beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” quotes one Forest Service manager, explaining Welcome Creek. Defenders of such areas believe the wilderness system has too often been treated as a second national park system, stressing the spectacular “rocks and ice” of the alpine peaks while neglecting the lower undisturbed forests and wildlife habitats that are vanishing most rapidly because of the commodities they can produce.

A decade ago, retired Montana forester William R. “Bud” Moore described the quiet beauty of Welcome Creek in the journals he kept during an autumn and winter spent in an old mining cabin in the heart of the area: “Each intimate twist in the trail-there are many-opened sudden new vistas, mini-worlds they were, each different from the last, expanding ahead then closing behind a giant rock point or spruce tree as I ambled on through the spell of evening hush.”

Later, in an informal report to the Missoula district ranger, Moore summed up the essence of the Welcome Creek Wilderness: “In the area’s little-disturbed ecosystems lies a rich resource of wildness. Canyon solitude, brawling streams, diverse forests, and their associated wildlife combine to form the wild resource.”

The geology of Welcome Creek is typical of the Sapphire Mountains, with rounded ridges of ancient Precambrian seabed rocks that were baked into argillites and quartzites deep in the earth’s crust. Some geologists believe the entire range was formed by earth pushed aside when the Idaho batholith welled up more than 70 million years ago to form the Bitterroot Range a dozen miles west. Scattered granitic outcrops in the Welcome Creek Wilderness tell of molten rock injected from below, creating both the small pockets of gold that lured the early miners and the scattered sapphire deposits 50 miles south that give the mountain range its name. Dark granitic rocks loom along Rock Creek at the Dalles, near the mouth of Welcome Creek, where a suspension footbridge spans Rock Creek at the main wilderness entrance. Other granites occur near the top of 7,240-foot Cleveland Mountain, on the western rim of the wilderness, where the Cleveland Mine once worked an underground vein.

Gold was first discovered in Welcome Creek in 1888, and the early pick-and-shovel miners quickly extracted most of it from “placer” or streambed pockets eroded from higher veins. The mining boom revived in 1895, with news of gold strikes just across the Rock Creek canyon on Quigg Peak. A town known as Quigley sprang up on the northeastern edge of the Welcome Creek Wilderness, opposite Sawmill Creek, and promoters secured $1.5 million in backing from speculators whose ranks included President Grover Cleveland. But the boom ended abruptly when investors learned that the discovery was a fraud.

The Welcome Creek mining era was brief, but according to one local historian it yielded one of the largest nuggets ever found in the state, one that must have approached 1.5 pounds and would have brought about $10,000 on today’s market. Somehow it escaped official record. In all, Welcome Creek yielded only about $30,000 in gold, at turn-of-the-century prices. Several mining claims remained active through 1983, but none proved promising enough to justify develop ment. The claims expired with the end of the I9-year grace period the Wilderness Act mandated for miners.

When the mines were abandoned in about 1900, lower Rock Creek briefly became a haunt for outlaws and horse thieves, notably one Frank Brady, who was pursued during the summer of 1904 and finally killed in a Thanksgiving Day shoot-out at an old Welcome Creek cabin. Thereafter, the Welcome Creek country slumbered for 60 years until the Forest Service pushed a logging road into the upper flanks of Welcome Mountain in the mid-1960s, at a cost of $90,000. Major clearcuts were mapped out across the Welcome Creek headwaters, and the timber harvest rights were sold in 1969. When the Forest Service inventoried its potential wilderness lands in 1971, Welcome Creek was overlooked. Conservation groups, worried about potential impacts of roads and logging on Rock Creek, filed a broad appeal questioning government logging plans for the Rock Creek watershed. The action led to formation of the Rock Creek Advisory Council, an unprecedented citizen advisory group with a federal mandate to help the Forest Service redraw its plans in order to protect the watershed. The council included ranchers, miners, sportsmen, businessmen, and representatives from conservation groups and the timber industry. All agreed that watershed protection should be the top priority in the drainage.

Meanwhile, sportsmen took new interest in Welcome Creek when a landmark Montana elk and logging study began documenting the animal’s habits in the northern Sapphires and a half-dozen other parts of the state. The purpose was to learn more about how logging affects elk habits. Inadvertently, researchers discovered that Welcome Creek is a favorite summer haunt and migration route for many of the roughly 300 elk that winter on the state’s Threemile Game Range, in the western foothills of the Sapphires.

By 1977, Welcome Creek had been proposed ,in Congress as a wilderness area. Conservation groups, pressing for a new inventory of roadless lands, cited it to illustrate the shortcomings of the first one. Time and economics had caught up with the Welcome Creek timber sale, which had been extended three times, transferred from one company to another, and reduced in size. When its transfer to a third firm was proposed, the Forest Service canceled the sale, and wilderness designa tion quickly followed.

Though mundane to some, Welcome Creek offers a glimpse of the Sapphire Mountains as they were before modern management. Moore views it as “a major island in an ocean of roads and logged areas.” It may turn out to be a scientific treasure for future foresters interested in measuring the long-term changes that logging and management produce on tree growth, soil fertility, wildlife diversity, watershed protection, and evolutionary change. A system of natural research areas is taking shape in Montana to fill the scientific gap, but the areas are small and scattered. Some believe there should be a representative wilderness area like Welcome Creek in every mountain range in the state.

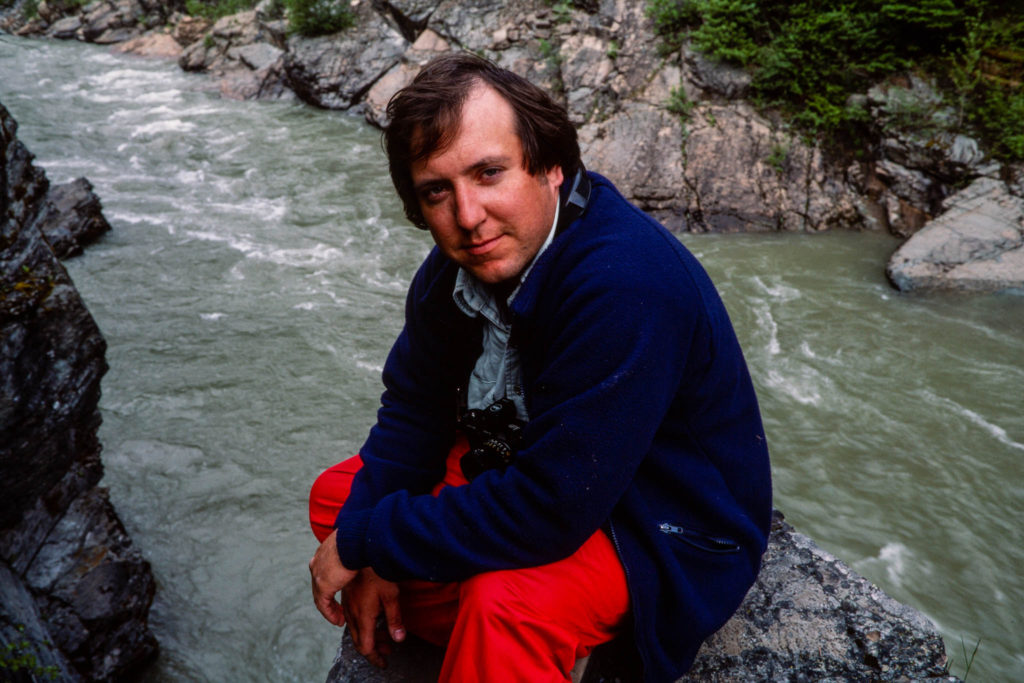

Don Schwennesen covered northwestern Montana regional news and outdoor issues through the 1990s for the Missoulian. He became editor and manager of the weekly Bigfork Eagle in 1998, after it was acquired by Lee Enterprises, the Missoulian’s parent company. He retired in 1999 and celebrated the end of the millennium on a six-month camping trek around Australia and New Zealand with his wife, Rose. Upon return, he joined as an active partner in his wife’s real estate business, re-starting a second career that began when he was first licensed in 1972. He continued to advocate for conservation and land-use planning, serving in leadership roles with Citizens for a Better Flathead, a local advocacy group. He and Rose also found time for travel, including annual extended backpack trips into Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. They celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2019, and they remain active in real estate, while supporting a variety of land-use and conservation causes. Their small orchard-vineyard still produces organic sweet cherries and grapes at the homestead overlooking Flathead Lake, and their passions range from travel, camping and wilderness hiking, to international folk dancing, geology/rockhounding — and of course grandchildren.

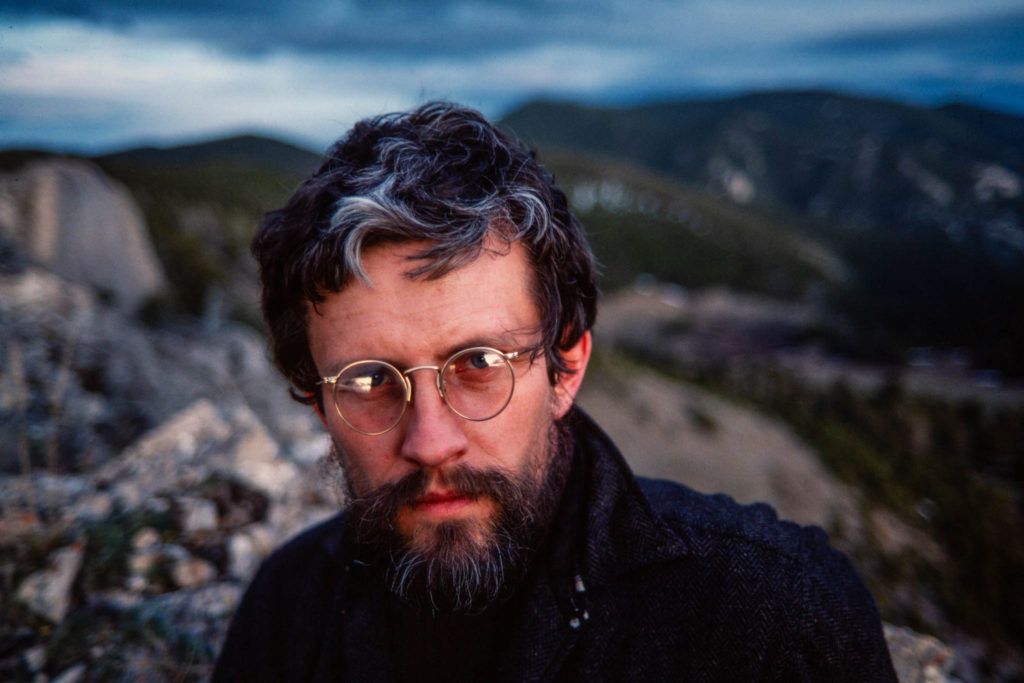

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.