By Steve Woodruff | Photographs by Carl Davaz

White Cap Creek beckons beneath a cloudless August sky. Its transparent water dances and tumbles into quiet pools where the dark forms of Chinook salmon once rested after their long journey from the Pacific Ocean. The salmon have all but disappeared, and today most of the shadows crossing the creek’s cobblestone bottom fall from tall cedars and ponderosa pines.

Sooty scars brand the red-trunked pines as survivors of a recent forest fire — a blaze that left patches of charred snags rising from a mosaic of new green underbrush and tiny pine seedlings. A new generation of forest is sprouting in this scorched corner of the Selway-Bitterroot Wilderness, and with it grows new understanding about fire and its importance to America’s wild lands.

This 1,337,910-acre area straddling the Montana-Idaho border refutes one of the most basic ideas about wilderness protection. In the Selway-Bitterroot, foresters are discovering the beneficial role forest fires play in rejuvenating and sustaining the wilderness. Here, as in many of the nation’s wilderness areas, people are learning the difference between protecting the land and perpetuating nature.

The wilderness soars above Montana’s Bitterroot Valley. The glacier-sculptured Bitterroot Range rises abruptly, its mountains made of granite, gneiss, and schist heaved skyward from deep within the earth. Great east-to-west canyons are gateways that lead high into the mountains, reaching beyond the eastern buttress of the Bitterroots to clusters of small, icy lakes. Dozens of 8,000-foot-plus mountains, including the 10,157-foot Trapper Peak and massive 9,983-foot El Capitan, tower over the rugged landscape.

From the Bitterroot Divide, the wilderness drops westward into Idaho, falling thousands of feet to the wild and scenic Selway River and the Lochsa National Recreation River. Only a narrow road corridor separates the Selway-Bitterroot from Idaho’s huge Frank Church-River of No Return Wilderness to the south.

The Selway-Bitterroot’s character changes with the terrain. A hot summer dominates the low-lying river canyons of Idaho, where rattlesnakes thrive in the blazing 100°-Fahrenheit temperatures. Elsewhere, dense jungles of lodgepole pine give way to parklike stands of ponderosa. Pockets of spruce and fir lead to scattered alpine larch in the high country.

Green meadows, splashed with color by Indian paintbrush, beargrass, and lupine, surround alpine lakes where delicate shooting stars poke their purple heads above muddy shores. In the rocky heights, little else survives but scattered colonies of green and black lichen . Frigid weather grips the wilderness in winter, loosening its hold over the higher elevations for only a few summer weeks.

Large numbers of elk make their home in the timbered canyons and bench lands. Their eerie autumn bugling pierces the wilderness silence, and their hooves carve the only trails that penetrate the Selway-Bitterroot’s most remote corners. Elsewhere, human footprints share wilderness trails with the tracks of moose and black bears. Cautious, but curious mule deer investigate the lakeshore camps that disturb their summer range, and silhouettes of brown bats chase swarms of mosquitoes in the night sky. The Selway- Bitterroot is rich in wildlife. In all, eight varieties of fish, nearly 60 species of mammals, and perhaps 200 different birds inhabit this wilderness.

The Selway-Bitterroot inspired some of the nation’s first wilderness-protection efforts. Bob Marshall, who once explored this region, lobbied for its preservation. The Forest Service first set aside portions of the Bitterroot, Lolo, Nezperce, and Clearwater national forests as the Selway-Bitterroot Primitive Area in 1936, and the area was among the first designated for protection under the Wilderness Act of 1964. Today, the Selway-Bitterroot’s boundaries encompass one of the largest wild lands in the country.

But the very act of protecting the Selway-Bitterroot poses a threat to the wilderness. Closure of the area to roads, logging, and other types of development is an essential part of maintaining the Selway-Bitterroot’s wilderness character. However, when protecting the area from fire, one of the primary forces of nature, the Forest Service went too far.

For decades, the Forest Service and other government agencies worked quickly to extinguish all wildfires. The goal was simple, the tactics aggressive: control any fire, no matter where, when, or how it started, by 10 a .m. the day after it began. Fire was an enemy attacked by land and air, with pulaskis, axes, bulldozers, and bombers. When protecting commercial timberland, relentless fire-suppression efforts can save precious natural resources. But in places where fire is part of a natural cycle, fire fighting is disruptive.

Years ago, some foresters noticed changes in the Selway-Bitterroot. Forests long dominated by ponderosa were slowly tilling in with other species of trees. Wildlife, once abundant, was increasingly hard to tind. Insect pests, such as the mountain pine beetle, were spreading farther and faster. People had changed the Selway-Bitterroot with isolated homesteads, decimated salmon runs, and dammed mountain lakes. But these developments were almost insignificant compared to the sweeping effect of fire fighting.

The changes were hardly surprising. The forests here and in much of the northern Rocky Mountains were born of fire. Ponderosa pine, with its thick bark, is especially adapted to periodic fires that clear away the competing understory. Frequent fires also prevent forest litter from accumulating, so there is seldom enough fuel to carry threatening flames to the upper reaches of the tall pines. Most wildfires are small, usually burning one-quarter acre or less. Even the large fires burn in spots and spurts that leave interlaced patches of burned and unburned forest. The result is diversity, an intermingling of old and new growth, of fire dependent and fire-susceptible vegetation.

Fires help cleanse the forest of pests, such as pine beetles and other insects. One scientific study showed that insect epidemics in the Bitterroot Range grew worse after settlers arrived in western Montana and began fighting natural fires. Even the Selway-Bitterroot’s elk herds have adapted to fire. Elk feed on the brush fields that spring to life in the wake of large fires.

Huge fires that burned the area in 1910, 1919, and 1934 created forage for expanding numbers of elk. The brush eventually grew too high for the animals’ reach or was crowded out by other plants. Without fire to stimulate growth of new forage, elk numbers began to decline. The Selway-Bitterroot was being altered by man and his attempts to exclude fire.

In the 1940s, a group of foresters suggested allowing fire to play a more natural role in the Selway-Bitterroot. But foresters scrapped the idea after contemplating the public outrage such a policy might produce. The National Park Service in 1968 began allowing some fires to burn in California’s Sequoia and Kings Canyon national parks in hopes of restoring natural conditions to high-altitude forests. But in America’s wilderness areas, the fight against fire continued.

Fire suppression in the wilderness is a tactic for delaying, not controlling, nature’s will. By stopping natural fires from burning, man merely allows forest fuels to build, creating the potential for fires of greater intensity. “Mother Nature is pretty relentless,” observes Mick DeZell, fire management officer for the Bitterroot National Forest in Hamilton. ” She’s going to get it done sooner or later.”

The Wilderness Act of 1964, the blueprint for America’s wilderness-preservation system, calls for protection of areas “affected primarily by the forces of nature, with the imprint of man’s work substantially unnoticeable.” Foresters read the act, looked at the unmistakable imprint their fire suppression was making on the Selway-Bitterroot, and decided to take another look at the idea of letting fires burn in wilderness.

America’s battle against forest fires began in earnest in 1910 after a series of large fires swept through much of western Montana and northern Idaho. It took another fire, burning 63 years later along the Selway-Bitterroot’s White Cap Creek, to kindle new ideas about fire and its role in nature.

Two enterprising Forest Service employees, Bob Mutch and Dave Aldrich, hiked into the White Cap drainage in 1970 to begin work on a project that proved fateful: an experiment showing that fire helps, not harms, the wilderness. The two men conducted an exhaustive study of the area and wrote a plan for allowing naturally occurring fires to burn. After their superiors endorsed the plan, they waited for nature to test their theory.

The wait ended August 10, 1973, when a bolt of lightning sparked a fire near Fitz Creek, a tributary of White Cap Creek. “The easy decision would have been to go in and put the fire out. That’s what we’d been doing,” Mutch says. “But that wasn’t the right decision.”

Surrounded by skeptics and fire-horse foresters who described fire with words like holocaust and catastrophe, the Forest Service watched and waited. The fire burned for 43 days and nights, searing 1,200 acres. In some spots, the blaze wiped out everything; in others it was hard to tell there had been a fire. The fire crawled and smoldered, flared and raged , leaving an irregular pattern in its wake.

The fire brought new life to the White Cap. Blue grouse began feeding in the burned area while smoke was still rising from smoldering logs. After the fire, redstem ceanothus, a favorite elk food, had sprouted at the incredible rate of up to 80,000 seedlings an acre. Before the fire, the area had only scattered clumps of ceanothus.

Today, Mutch strides along the White Cap trail and marvels at the change. “I used to fall asleep walking down this trail,” he says. “Since the fire, there’s something new around every bend.” He pauses by a large ponderosa and reaches into his knapsack for a faded snapshot. The picture shows the tree, a decade earlier, blackened by fire and surrounded by scorched earth. The tree shows little sign of damage today. The fire scars have nearly healed, and the reddish trunk stands above a carpet of ocean spray and ninebark. “Fire is a process that has sculptured these hills for eons,” he says. “Now we’re perpetuating a wilderness resource as it should be.”

Wilderness scholars and the public were quick to endorse the natural-fire philosophy once it was explained. Sportsmen discovered an increase in elk and other wildlife populations near areas that had burned, and hikers who came to the Selway-Bitterroot enjoyed a wilderness experience in a more natural setting. Lightning-caused fires are now allowed to burn in nearly 9 million acres of national forest wilderness areas, including most of the wildernesses in Montana. Since the 1973 Fitz Creek fire in the Selway-Bitterroot, more than 1,200 separate fires have been allowed to run their course over 190,000 acres of wilderness and national park lands.

Yet man has not relinquished all control of the wilderness. Only fires that occur during specified conditions are allowed to burn. If weather and fuel conditions indicate that a fire might spread to commercial timberland outside wilderness or that smoke from the fire could create serious pollution in nearby cities, the Forest Service launches its attack.

Some foresters now suggest that wilderness fires should be kindled by man under prescribed conditions and not left to the uncertainties of nature. So-called planned ignitions might better control fires and allow wilderness managers to erase the undesirable legacy of decades of overaggressive fire suppression.

New attitudes about fire are just an example of the changing ideas about man’s role in the wilderness. Wilderness managers in the Bitterroot National Forest are removing trail registers, not replacing wilderness signs that become damaged or lost, and drastically cutting trail maintenance and construction. A hands-off philosophy of wilderness management is slowly gaining popularity.

A less naive view of man’s niche in the wilderness is emerging from the lessons learned along White Cap Creek, a view that reflects a better understanding of what makes wilderness wild. Man cannot control the natural forces that shape wilderness; he can only interfere. Wild places like the Selway-Bitterroot exist not only because they are protected by man, but also because they are protected from him.

Steve Woodruff covered natural resources and the environment for the Missoulian through the mid-1980s, after which he served as the newspaper’s longtime editorial page editor. After stepping off from the newspaper in 2007, he continued writing about natural resources and worked as a strategic communications consultant for wildland- and wildlife-conservation organizations, and he taught journalism at the University of Montana. He also served as senior policy and communications manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Montana-based Northern Rockies and Pacific Regional Center, working on bison, bighorn sheep and grizzly bear restoration and a variety of public land-and-resource issues. Woodruff retired in 2017, lives in Missoula with his wife, Carol, and continues to explore Montana’s wilderness areas.

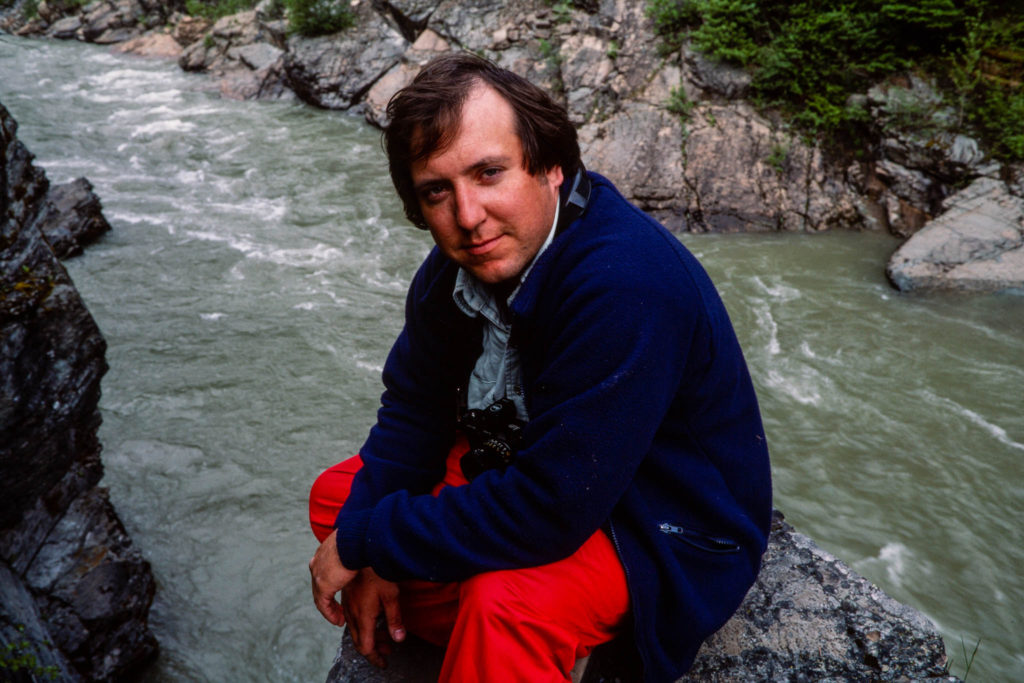

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.