By Steve Woodruff | Photographs by Carl Davaz

Upper Red Rock Lake comes alive as the first golden streaks of dawn ease over the Continental Divide. A lesser scaup noisily announces the morning, accompanied by mallards quacking along the shore. Sandhill cranes cry shrilly as they pace the rolling grassland overlooking the lake. Nearby, pronghorn antelope sprint across the sagebrush-covered floor of the mountain valley. From one of the lake’s secluded bays, two trumpeter swans add their deep, resonant bugling to the growing cacophony. The great swans unfurl their broad wings and spring into the morning air, winging high over Montana’s Red Rock Lakes Wilderness.

The swans rise over a land of lakes, marshes, and high prairies hemmed by the towering Centennial Mountains and the gentle foothills of the Gravelly Range. Red Rock is one of the last strongholds of the trumpeter swan, among the rarest and most majestic birds on the continent. Once pushed to the brink of extinction, the swans, like many of America’s wildest creatures, have found a haven in the wilderness.

Montana has three wildlife wildernesses: Red Rock Lakes, UL Bend, and Medicine Lake. The diverse areas are part of the national wildlife refuge system and are managed by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service more for the benefit of birds and animals than for the pleasure of people. In a world where man’s activities have changed much of the natural environment, wilderness areas like these contain the undisturbed habitat that many species of wildlife need to survive.

Nestled in Beaverhead County’s strikingly beautiful Centennial Valley, about 50 miles west of Yellowstone National Park, Red Rock is a 32,000-acre wilderness within a 40,000-acre national wildlife refuge. Nearly all the wilderness is covered by water. The large, shallow Upper and Lower Red Rock lakes are the heart of an extensive system of marshes tied together by meandering Red Rock Creek. From the 6,600-foot valley floor, the wilderness rises to the crest of the 10,000foot-high Centennials, a rare east-to-west mountain range.

Red Rock is a drive-in wilderness. A gravel road skirts its edge, where campgrounds, complete with picnic tables and barbecue pits, overlook the marsh. Despite the relatively easy access, this is one of the least visited wilderness areas in Montana. Few of the 6,000 people who find their way into this isolated valley each year venture beyond the edge of the wilderness. Although game and cattle trails wander through the dryland portions of the area, the short boat ramps leading onto Upper and Lower Red Rock lakes are the only semblance of developed trails. The proposed Continental Divide Trail would parallel the southern boundary of the area, but the best means of exploring Red Rock’s wilderness interior is by canoe. Boats are allowed on Upper Red Rock Lake only after July 15, when the waterfowl nesting season ends. Motorboats are permitted on Lower Red Rock Lake in the fall, a concession Congress made to the duck hunters who had boated on the lake for decades before it became a wilderness. Boating is prohibited on the lower lake during the spring and summer to protect nesting swans.

For about 5 months each year, the valley is virtually locked away from the rest of the world by 3 to 16 feet of snow. The few people who live in Lakeview, a rustic resort town and Fish and Wildlife Service outpost on the southern fringe of the refuge, are a 30-mile snowmobile ride from civilization during the long winter.

Red Rock’s unusual melding of native grassland, marshes, and mountains creates habitat for a diverse community of wildlife. Moose roam the Centennials and adjoining Henrys Lake Mountains. The moose population increases greatly in the fall as animals from surrounding mountains drop into the wilderness to winter in the willow thickets on the valley floor. The dryland areas bordering the marsh are home to 300 to 500 pronghorns, a large herd for the relatively compact area. Mule deer, elk, and black bears inhabit the forests, joined by an occasional grizzly drifting in from Yellowstone Park or the nearby Targhee National Forest of Idaho.

Most visitors come to fish Red Rock Creek or several small lakes that are in the refuge, but outside the wilderness. The creek holds one of Montana’s last populations of native arctic grayling. Grayling thrived throughout the upper Missouri River and its tributaries until pollution and sedimentation in streams and rivers forced the sail-winged fish to retreat, like the trumpeter swan, into pockets of still-suitable habitat. Nearby, Elk, Culver, and MacDonald lakes boast trophy-sized rainbow, eastern brook, and Yellowstone cutthroat trout. The wilderness lakes and ponds, inhabited mostly by small ling and suckers, are closed to fishing to protect wildlife from disturbance by humans.

Red Rock is perhaps most remarkable for its bird life. Bald and golden eagles, sora rails, peregrine falcons, and 23 kinds of ducks and geese are among the 215 species of birds found in the wilderness. The marshes offer a resting spot for tens of thousands of migrating waterfowl each year, while providing enough nesting habitat to produce as many as 8,000 ducks each summer. But it is as a sanctuary for trumpeter swans, the largest birds in North America, that Red Rock is best known.

This area was preserved for the sake of the trumpeters, which are bigger, deeper-voiced cousins of the more common tundra or whistling swans. The great birds were once so numerous throughout the country that their snowy plumage was used to make powder puffs and writing quills. But market hunters killed them by the thousands, and an expanding nation of settlers drained their marshes and destroyed their habitat. In 1935, with the 70 known remaining swans surviving within a short radius of the Centennial Valley, the federal government created Red Rock Lakes National Wildlife Refuge. And in 1976, Congress added another layer of regulatory protection to the irreplaceable marsh by naming it a wilderness area.

Abandoned homesteads weathering on the edge of the wilderness are testament to the hard life settlers found when they arrived here a century ago. This valley is no more hospitable to the trumpeter swan than it was to the homesteader. Red Rock provides only marginal habitat. The winters are long and severe, and the short summers allow only one chance a year for nesting. Yet the area offers the wary, easily disturbed birds what they need most: safety and security. The swan population rebounded dramatically on the wilderness preserve. The regional trumpeter population in Red Rock, Yellowstone Park, and the Henrys Fork of the Snake River peaked at about 670 birds in 1958.

But the regional swan population and production of young, called cygnets, have declined markedly in recent years, a trend biologists cannot fully explain. Poor weather for nesting accounts for part of the decline. Although a nesting pair of swans hatches two to seven cygnets every summer, only a fraction survive. About one-half the region’s cygnets are raised in Red Rock, with about 30 surviving to flight each year. However, healthy populations of trumpeters have been discovered in Alaska and Canada, and fear for the bird’s extinction has eased.

Most of the swans spend their lives near Red Rock, no longer migrating to warmer winter climes. More than 250 swans winter on Culver and MacDonald lakes on the eastern end of the refuge. Unlike the vast wilderness marsh, the two small lakes are spring-fed and do not freeze. However, the area lacks enough natural food to sustain the swans through the winter, so the Fish and Wildlife Service feeds them grain.

Red Rock’s wilderness designation protects it from mining and petroleum exploration. Wilderness restrictions also guard the timbered slopes against logging. Although government grazing allotments allow cattle to feed side by side with pronghorns, ranchers are prohibited from using motor vehicles to tend their herds. All these protections help preserve the tranquility so important to the stately trumpeters. Yet for the swans, and for many other types of wildlife that live in wilderness areas, strict regulations can hurt as well as help.

Although Congress gave the Fish and Wildlife Service permission to use a motorboat for capturing and banding swans, wildlife in wilderness must be managed without leaving man’s imprint on nature. For example, the many miles of fences that separate cattle from swan habitat must be maintained without the aid of vehicles or power tools. Without the help of modern equipment, prescribed burning to improve habitat is difficult, at best. Even the winter feeding, which may be essential to the swans’ survival, seems to clash with the spirit of the Wilderness Act. However, an attempt to restore natural conditions by forcing the birds to seek more suitable wintering grounds failed: when the winter grain supplements were withheld, about 30 swans died before refuge managers abandoned the experiment and resumed the feeding.

Some biologists have suggested that rescinding Red Rock’s wilderness designation might allow better, more intensive wildlife management. But, aware that the unprecedented step would take an act of Congress and create a political firestorm, agency officials are not seriously pursuing the idea. Instead, wildlife managers at Red Rock are concentrating their efforts on understanding more about the swans and the wilderness where they live. One management project involves rebuilding swan nests atop floating platforms to protect eggs from flooding. The platforms promise to increase the swans’ nesting success without requiring humans to alter significantly the wild environment.

Although there is hope for the trumpeter’s survival, chances may be limited for restoring widespread populations of the birds in the continental United States. Biologists have succeeded in transplanting some swans in other areas where the birds once lived. But few of the relocated swans prosper. People have ruined too many of America’s natural places, leaving little more than the marshy wilderness of Red Rock Lakes where the trumpeters can sing their wild song.

In the not-so-distant past, all Montana was a wilderness for wildlife, especially the broad, rolling plains east of the Rocky Mountains. Tremendous herds of bison roamed the prairie, along with elk, wild sheep, and grizzlies. But America’s westward expansion destroyed much of the wilderness and its wild inhabitants. Market hunters all but wiped out the bison. The native prairie grasses, which had supported an amazing diversity of life for thousands of years, fell to the homesteader’s plow. Settlers pushed the elk into the mountains and drove the Audubon sheep to extinction. The newcomers also killed or chased from the land the Indians who for so long had shared the prairie with the wildlife.

On their way West, uncounted numbers of settlers crossed an area known as UL Bend, a narrow peninsula along a sweeping hairpin turn in the Missouri River. Located in Phillips County, midway between Lewistown and Glasgow, UL Bend is now a 20,800-acre wilderness area. It lacks the spectacular landscape of Montana’s mountain wildernesses but possesses a harsh beauty. Short prairie grasses wave in the incessant wind amid clusters of prickly pear cactus. Sagebrush and greasewood cover broad flats, where patches of snow-white alkali bake in the sun. Small forests of scrawny ponderosa pine and juniper fill a winding series of coulees.

The land in the wilderness interior rolls gently, but the serpentine edges of the area fall ruggedly to the shores of Fort Peck Lake, the impounded waters of the Missouri River. UL Bend lies a short distance downstream from the last free-flowing section of the 2,500-mile-long Missouri. The lake, a mile wide at its narrowest point, forms a broad moat protecting 32 miles of shoreline on the eastern, southern, and western boundaries of the wilderness. Thousands of acres of federal and state land adjoin the northern boundary. From the lakeshore at 2,250 feet above sea level, the land rises steeply. But the highest point in the area, near the southern end of the peninsula, reaches only 2,700 feet.

UL Bend is the legacy left by glaciers. During a series of ice ages, thick sheets of ice pushed the Missouri River out of its historic channel, which is now occupied by the Milk River, 60 miles to the north. The Missouri carved its present channel along the southern face of the glaciers, detouring in a great bend around the finger of ice that extended over what is now UL Bend. The glaciers covered large expanses of Bearpaw shale, an easily eroded type of decomposed bedrock. Water melting from the southern face of the glaciers flowed into the Missouri River, carving deep ravines as it tumbled across the Bearpaw shale.

The ravines form today’s Missouri River Breaks. The Breaks and prairie appear barren at midday but change dramatically when late-afternoon shadows fill the swales and coulees. Evening brings the wildlife out of hiding to feed on grasses and shrubs. This narrow peninsula supports a surprisingly large population of mule deer, as well as white-tailed deer, pronghorns, and elk. A variety of birds and smaller animals, from burrowing owls to prairie dogs, inhabit the area. Yet the UL Bend is more than a wildlife refuge; this remarkable wilderness is a portal into Montana’s past.

A thick layer of whitened bones at the base of a cutbank tells of a time, perhaps 500 years ago, when herds of American bison thundered across this plain. The bones undoubtedly mark a buffalo jump, where Indians killed bison by stampeding them over a steep embankment. The last bison vanished from this area more than a century ago, but their weathered horns still remain scattered across the sage flats. Large circles of rocks, undisturbed for centuries, mark the spots where Sioux, Blackfeet, and Crow tribes pitched their tepees when they came here to hunt.

The earth, especially along the lakeshore, contains evidence of life in a much earlier time. The ground holds a wide array of fossils, including wood, shellfish, and bones. Fossils, Indian artifacts, and other historic items are for the looking, not taking, however; Fish and Wildlife Service regulations prohibit collecting them.

The Lewis and Clark expedition found an area teeming with wildlife when it passed UL Bend in late May 1805. The party camped at the mouth of the Musselshell River, just across the Missouri River from the southern tip of UL Bend’s peninsula. As the explorers approached UL Bend, the expedition’s Sergeant John Ordway noted in his journal that “we saw large gangs of elk, which are getting more plenty than the buffalo.” The journals of Lewis and Clark say the party also saw many Canada geese and killed several grizzlies near UL Bend.

Although the elk and geese were once driven from the plains, both were reintroduced in the 1950s, and small populations have been restored. The UL Bend and the surrounding Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge are the only places in Montana where elk still occupy their native prairie year-round. Grizzlies, however, retreated to the mountains, never to return to their home on the plains.

People tried but failed to tame this piece of wild prairie. The steamboats that began plying the Missouri River in 1859 stopped at the UL Bend, which was known then as the Great Bend of the Missouri. The steamboats discharged passengers on the area’s eastern shore, giving river-weary people a chance to stretch their legs with a 2-mile walk across the peninsula. The steamboats picked up the passengers again on the western shore after chugging around the bend. Today, a number of faint trails cross the peninsula at its narrowest point, perhaps the pathways left by some of the earliest Montanans.

Ranchers and homesteaders tried to settle here. The area’s name comes from the UL brand borne by the cattle that once ranged over the peninsula. But the harsh climate and rough terrain of the Missouri River Breaks defeated those who tried to stake claim to the wilderness. “Man has never been very successful at doing anything in the Breaks that was able to overcome what Mother Nature wants to do here,” says Jim McCollum of the Fish and Wildlife Service.

On the area’s western ridge, grass almost covers a wooden hay rake, an artifact hauled up from the homesteads that were obliterated when Fort Peck Lake flooded the Missouri River bottoms in 1941. A cowboy’s old line camp, consisting of a pair of aging log cabins, still stands on a low hill overlooking Jim Wells Creek, near the northern end of the wilderness. Water, potable but soured by minerals, bubbles from an artesian well a short distance from the cabins. Two rusting wire fences, which the Fish and Wildlife Service hopes to remove someday, bisect the area.

Although the wilderness contains no maintained trails, several twin-rutted tracks wend through the area. Horse-drawn wagons probably laid down the first tracks, but four-wheel-drive vehicles etched them firmly in the soil. The area was open to vehicles until it became a wilderness area in 1976.

An occasional survey marker pokes above the low sage, miniature memorials to a grandiose scheme that would have turned the UL Bend into a nesting marsh for waterfowl. When the Fish and Wildlife Service established the UL Bend National Wildlife Refuge in 1967, its officials envisioned crisscrossing the flats with a series of low dikes, then flooding the area with water pumped from the Missouri River. Nine years later, with the project doomed by economic reality, the agency asked Congress to designate the area as wilderness.

Although UL Bend’s wilderness designation came without much organized public support or opposition, the area later became the focus of a minor political skirmish in Congress. Led by Montana Sen. John Melcher, Congress in 1983 pried open a narrow corridor through one comer of the wilderness-an act that allows vehicles to travel one of the old jeep trails through the UL Bend to reach Fort Peck Lake.

Regardless of the road, the Fish and Wildlife Service figures that only about 4,000 people visit the UL Bend each year. Ease of access to UL Bend is fair to terrible, depending on the weather. In warm, dry weather, the wilderness is a 50-mile dirt-road drive from the town of Zortman, near Highway 191. After a heavy rain, the entire expanse surrounding UL Bend becomes a wilderness of gumbo, impassable even for four-wheel-drive vehicles.

UL Bend is at its best in late spring, when the prairie blooms with penstemon and yellow pea. Spring temperatures are balmy compared to the often-searing heat of summer and the sometimes-frigid cold of winter. But most wilderness visitors arrive during the fall, attracted by big game and upland-game-bird hunting seasons. The number of backpackers who explore UL Bend in a given year is minuscule.

For early settlers, UL Bend was a small obstacle on a long westward journey. Similarly, most of today’s Montanans and the tourists who visit the state pass the area by, choosing instead to search for outdoor adventures in some of the better-known mountain wildernesses. The rolling peninsula remains a quiet refuge for wildlife and an almost-for gotten reminder of Montana’s pristine past.

At another wildland remnant, Medicine Lake Wilderness, people are looking to the future. In the middle of a region dominated by intensive agriculture, the Fish and Wildlife Service is working to ensure the survival of a small enclave of northeastern Montana’s prairie.

The state’s smallest wilderness, Medicine Lake is a sample of the marsh-filled prairie that once stretched across northeastern Montana into Canada, the Dakotas, and Minnesota. After a century of farming and development, most of the wild prairies around Medicine Lake have been plowed and the marshes drained to make room for farms.

The 11,800-acre wilderness is within Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge in Sheridan and Roosevelt counties, located between Sidney and Plentywood. The wilderness consists of 8,700-acre Medicine Lake and the Sand Hills, a tiny relic of eastern Montana’s mixed-grass prairie. Medicine Lake is a point of transition between the short-grass prairie of central Montana and the tall-grass prairie of the Great Plains.

Islands in the lake support one of the continent’s largest remaining nesting colonies of white pelicans, big, graceful birds whose numbers have been depleted through pesticide poisoning and lost habitat. About 3,500 pelicans return to Medicine Lake each spring. The wilderness lake also offers occasional refuge to the perilously endangered whooping cranes, which pass by on their migration between their northern Canada nesting area and their wintering grounds on the Gulf of Mexico.

Great blue herons, double-crested cormorants, and two species of gulls also nest here, along with most species of North American ducks. Nesting waterfowl produce more than 25,000 ducks and nearly 1,000 Canada geese annually. Between 100,000 and 250,000 waterfowl sojourn at Medicine Lake during spring and fall migrations.

The lake portion of the wilderness offers migratory birds a much-needed sanctuary. On a continent where wetlands are disappear ing rapidly in the name of human progress, Medicine Lake and its islands offer birds and other wildlife a secure place to rest or nest. Perhaps the greatest danger to bird life here is the naturally occurring outbreaks of botulism. The periodic disease kills ducks by the thousands, forcing wildlife managers to invade the wilderness lake with motorboats to pick up carcasses in hopes of controlling its spread.

Where herds of bison once ranged, the grasslands surrounding Medicine Lake now support nearly 1,200 white-tailed deer. Pronghorns frequented the area less than a decade ago but have nearly vanished from the wilderness in recent years. Large numbers of sharp-tail grouse and ring-necked pheasants also live in the prairie portions.

Wildlife has almost always been plentiful here. Assiniboine Indians used to hunt bison near Medicine Lake. Today, the area’s plentiful deer, waterfowl, and upland game bird populations still attract hunters. Fishermen seek Medicine Lake’s northern pike. But many of the 9,000 people who visit here each year come simply to watch the birds and animals.

Medicine Lake occupies a portion of the Missouri River’s ancestral bed. The glaciers that forced the river to change its course to the south more than 10,000 years ago also leveled the land. When the glaciers retreated, they left behind huge pieces of buried ice that melted to form Medicine Lake and other prairie potholes. Windblown sand from Medicine Lake’s ancient shore later drifted into dunes, forming the foundation beneath today’s Sand Hills.

Although farming altered much of the native prairie pothole country, farmers and their livestock are playing an important new role in the protection of the pure native grassland at Medicine Lake.

Government agencies allow livestock grazing in most wilderness areas. At Medicine Lake, wilderness managers use an intensive grazing program to help native prairie grasses compete against an invasion of crested wheatgrass, an exotic variety introduced by homesteaders. Gene Stroops, manager of Medicine Lake National Wildlife Refuge, worries that crested wheatgrass from surrounding lands will eventually spread throughout the Sand Hills, effectively destroying the unique area.

The refuge is using cattle to combat the problem, allowing the animals to graze wheatgrass-infested areas early in the spring. Because wheatgrass greens up earlier than prairie grasses, the cattle eat it instead of the native varieties. Land managers move the cattle out of the area before the native species begin greening up, giving the plants a competitive edge against the wheatgrass.

Only time will reveal whether grazing is the ultimate defense for this parcel of native prairie. For now, the tactic seems to be working, and life for the birds and animals of Medicine Lake continues much as always. Nearby, traffic speeds by on state Highway 16. Farmers guide their tractors through surrounding fields, and oil rigs on distant ridges draw from the earth the lifeblood of energy-hungry America. But on spring mornings, sharp-tail grouse still gather near the lake, as they have for centuries, to perform their bizarre courtship dance. Pelicans still soar above the lake, and the lonesome calls of Canada geese roll across the low prairie. Here, as in all Montana wilderness areas, the denizens of the wild live in fragile harmony with man.

Steve Woodruff covered natural resources and the environment for the Missoulian through the mid-1980s, after which he served as the newspaper’s longtime editorial page editor. After stepping off from the newspaper in 2007, he continued writing about natural resources and worked as a strategic communications consultant for wildland- and wildlife-conservation organizations, and he taught journalism at the University of Montana. He also served as senior policy and communications manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Montana-based Northern Rockies and Pacific Regional Center, working on bison, bighorn sheep and grizzly bear restoration and a variety of public land-and-resource issues. Woodruff retired in 2017, lives in Missoula with his wife, Carol, and continues to explore Montana’s wilderness areas.

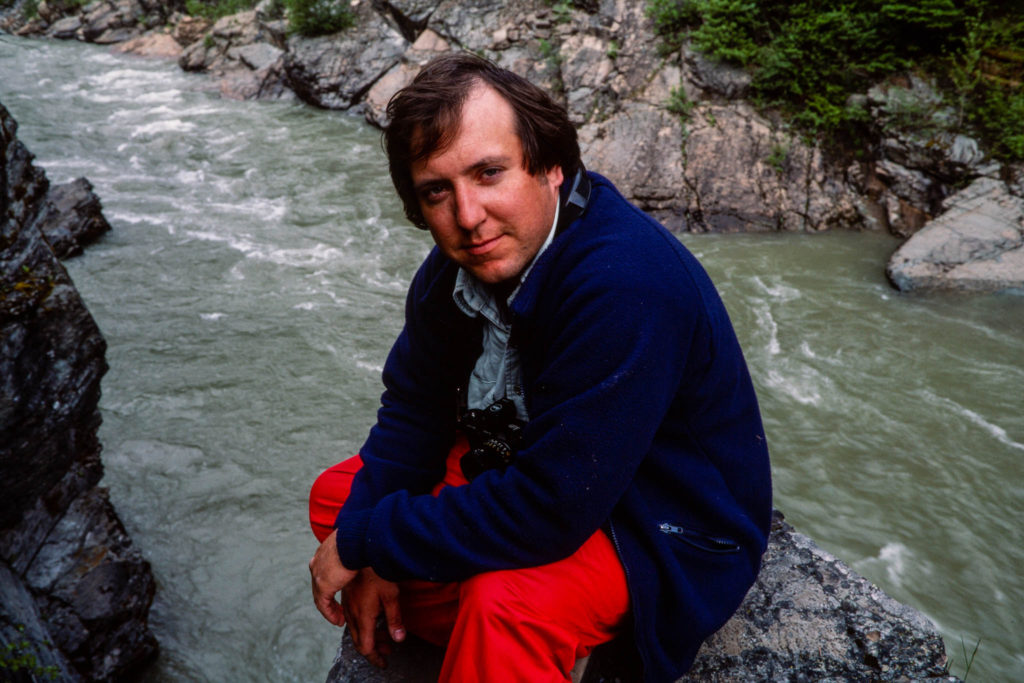

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.