By Don Schwennesen | Photographs by Carl Davaz

The bold peaks of the Mission Mountains crown a wilderness range unique in the West both in majesty and management. Soaring more than a mile above the farms and villages of the Mission Valley, the austere western front of the Missions forms one of the most striking mountain valleys in the Rockies.

But the range is more than a natural wonder. It is the first place in America in which an Indian nation has matched the federal government in dedicating tribal lands as a wilderness preserve. The Mission Mountains are two wilderness areas in one, divided along the crest of the range by the boundary of the Flathead Indian Reservation. East of the Mission divide, the Flathead National Forest manages 73,877 acres of wild country under the Wilderness Act of 1964. West of the divide, 89,500 acres have been set aside as a tribal wilderness by the Con federated Salish and Kootenai (Flathead) Tribes. Both wilderness areas are managed cooperatively and are open to everyone, but subtle differences in management style reflect tribal needs and traditions. For example, hunting in the tribal wilderness is reserved for tribal members, for whom it remains important both as a food source and as a link with tribal heritage.

The imposing western front of the Missions seems to reveal the wilderness peaks, basins, and headwalls in every detail; instead, it masks the true extent of an area 30 miles long and 6 to 10 miles wide. Trails of punishing steepness climb to hidden basins, big lakes, glaciated hanging valleys, and secret mountain passes. Delicate alpine flowers tremble in the wind atop broad ridges guarded by flanks so steep they defy human approach.

A dozen peaks over 9,000 feet rise from the southern end of the Missions, dominated by the great snowy head of 9,820-foot McDonald Peak. The tall central crest of the range catches the prevailing westerly winds, wringing down more than 100 inches of annual moisture, most of it snow. Alpine snowfields linger year-round, feeding a half dozen named glaciers and melting into icy streams and springs that purl through a remarkable 350 lakes, ponds, and pools.

Waterfalls are numerous. Mission Falls, cascading 600 feet down a rocky headwall in the shadow of the Garden Wall, is a landmark above the historic mission village of St. Ignatius. Most of the wilderness lakes were originally barren, cut off from migrating trout by steep rushing streams and falls that posed formidable natural barriers. Many high lakes freeze out in winter, but during the past 50 years trout have been established in about half of the more than 100 larger lakes. Native cutthroat predominate, but some lakes offer rainbow, brook, and even golden trout.

Elk, once famous for their trophy size in the central Missions, still inhabit much of the wilderness, notably the southwestern end. Goats are widespread, and a small band of bighorn sheep was introduced in North Crow Creek Canyon in 1979. Although hunting in the tribal wilderness is limited to tribal members, fishing and other wilderness activities are permitted for non-members who hold valid tribal recreation permits. State hunting and fishing licenses are also required.

An estimated 25 grizzly bears still range the Missions, and tribal managers place a high priority on their protection. Each summer, amid the snowfields and glaciers of McDonald Peak, the Mission grizzlies rendezvous in one of nature’s enigmatic cycles of life. Ladybugs and cutworm moths congregate by the thousands, perhaps emerging from hibernation or drawn together for reproduction. The grizzlies migrate to the mountain summit to feed on insects, and some bears linger near the cool snowfields for most of the summer. Concerned that the spectacle might draw curiosity-seekers, tribal managers have closed a 12,000-acre area around the mountain from mid-June through September. Signs posted at trailheads and strategic mountain passes warn visitors to respect the closure, and tribal managers patrol to ensure compliance. Biologists monitor the bears from an observation post on a nearby mountain.

In the eastern Missions, the Forest Service has imposed more-lim ited closures around the shores of heavily used Glacier and Cold lakes, where camps and fires are no longer welcome, due to impacts from past use. Fishing and day use are permitted.

Tribal managers still experiment with stocking fish in some lakes, and they occasionally use helicopters to shuttle supplies or track wildlife. They also have a more vigorous program for patrolling closures and checking popular trails. To help support management, the tribal government sells recreational use permits to non-members for $10 a year. A permit entitles the holder to hike, fish, camp, and enjoy most other recreational pursuits on tribal lands.

By contrast, the Forest Service has been reducing its wilderness presence in response to tighter federal budgets. Use fees have not been proposed, because of resistance from a public that believes it already supports wilderness management with its taxes. In 1983, no wilderness ranger was assigned to the Missions. In 1984, the agency decided to contract with the private sector for wilderness field work. A former seasonal wilderness ranger won the contract. The work includes clearing trails blocked by fallen trees, answering visitor questions, cleaning up litter, and instructing campers how to reduce their impacts. Some see the move toward contracting as a disturbing precedent that will further separate desk-bound foresters from the land they manage. Others believe it will help contain costs and reduce the bureaucracy.

The Forest Service maintains 71 miles of trail, and 45 miles climb the tribal portion of the Missions. Most are difficult for horse travel, which is discouraged to reduce competition with wildlife for the limited food available in the high country. The tortuous switchback trail up Post Creek, known as the “angel’s staircase,” is so severe that every year or two an unseasoned packhorse bolts and plunges to its death. The trail was closed for a week in 1983 due to the danger that one such carcass might attract grizzly bears. Unable physically to remove the carcass, tribal managers ultimately wrapped it with 100 pounds of spaghetti gel explosive and blasted it into oblivion.

The Mission Mountains Wilderness is rich in lore, much of it related to the Salish and Kootenai tribes. Like other Indians, they are heirs to a culture buffeted by outside encroachment and misunderstanding. Explorers Lewis and Clark called them Flatheads, but many tribal members insist today that their forefathers were mistaken for another tribe farther west whose members cosmetically flattened their foreheads. A peaceful people, the Flatheads were often raided by warlike tribes as they crossed the wilderness mountains to hunt buffalo on the Montana Plains to the east. Today, a few tribal elders can still trace the routes of old hunting trails that crossed the Mission Mountains. The wilderness mountains also held vision-quest sites, places still considered sacred, where young tribal members would fast alone and wait for a spiritual vision to guide them in later life. Other spots were summer camps where families gathered berries, roots, and medicinal plants. As white settlers arrived and the Indians were confined to the reservation, oldtime Missions outfitter Bud Chelf says, some trails were built as escape routes or travel ways for guerrilla wars of resistance that never came.

Opening of the reservation to homesteading coincided with devel opment of the Flathead Irrigation Project and construction of dams that created reservoirs and enlarged existing lakes along the western foot of the mountains.

In the early 1920s, Theodore Shoemaker of the Forest Service led railway parties and mountaineering groups on exploration trips into the Missions. The trips inspired the first map of the area, along with many of the lyrical names given to Mission landmarks: Lake of the Stars, Lake of the Clouds, Sunrise Glacier, Picture Lake, Daughter of the Sun Mountain, and Turquoise Lake. Other names, such as Mount Harding and McDonald Peak, leave some tribal members dissatisfied and may ultimately be abandoned in favor of Indian names.

In 1931, the eastern Missions became a Forest Service primitive area, and in 1936, the Flathead Tribal Council resolved to make the western Missions an Indian national park. But the park idea was stalled in Washington, D.C., where early wilderness advocate Bob Marshall was working for the Bureau of lndian Affairs to set aside wild areas on Indian reservations. Eventually he established 16 of them, but 15, including the Missions, were later declassified by tribes resentful of such federal intervention. Wyoming’s Wind River Reservation still has a wilderness, but the Flathead tribes take pride in having set aside the Missions on their own terms.

The edges of the wilderness contain a few areas that some believe could produce commercial timber. Logging has occurred inside the wilderness on low-lying tribal, Forest Service, and former railroad lands. The old Northern Pacific Railway once owned 30 percent of the eastern Missions, although the land was gradually exchanged for other forest land outside the wilderness. The Forest Service wilderness today includes about 2,000 acres logged under special authorization in the 1950s to salvage insect-killed timber. Logging has been proscribed since the Forest Service primitive area became a wilderness in 1964, but it is still a possibility within the tribal wilderness.

Tribal member Thurman Trosper, a former top Forest Service official, became the prime mover for the tribal wilderness in 1975 after his retirement. The Tribal Council endorsed the idea and retained the University of Montana’s Wilderness Institute to study suggested boundaries and draft a management plan for the area. The final plan, which was drafted by David Rockwell, was adopted by the council in 1981 when the Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness became a reality.

A past national president of the Wilderness Society, Trosper has wandered the Missions since he was a teenager. He resolutely opposes scarring the face of the Missions with permanent roads, but, living on a reservation where jobs are scarce, he is mindful of the potential value of the 4 million board feet per year of timber the edges of the tribal wilderness could yield.

“An Indian wilderness is not a federal wilderness,” he notes, adding that the tribes still “have the option to take timber.” Horse-loggers cleared the lower slopes of the Missions in the early 1920s on North Crow Creek, but the scars healed in the relatively stable argillitic soils of the Missions. He believes careful horse-logging may still be an option in the wilderness. Logging on other tribal lands is an economic mainstay for the roughly 3,000 tribal members who live on the reservation. An equal number have left to find jobs elsewhere. The Flatheads are a minority both on their reservation and in their wilderness. Out of 4,000 wilderness visitors in summer 1977, only 5 percent were Indian.

Some management issues reach beyond the wilderness boundary, a dilemma illustrated by the Mission grizzlies. Most wilderness areas protect only scenic, high alpine country and contain few lowlands. Forested foothills and valley lands are excluded because they lack spectacular scenery and are valued for timber production, farmland, or subdivision. But the austerity of the high mountains limits survival for animalsjust as it does for humans. The grizzly hibernates and summers in alpine country but in the spring and fall descends to valley stream bottoms, where food is more plentiful.

Today grizzly feeding areas are limited on both sides on the Missions. To the east, in the Swan River Valley, timber sales and valley farmsteads are expanding inexorably, although managers try to balance the bears’ need for cover with timber harvests that may increase the forage plants used by the bears. Only one or two timbered travel cor ridors remain across the valley to link the Mission bears with the larger grizzly population roaming the Bob Marshall Wilderness complex.

Along the western front of the Missions, where timbered stream bottoms thread out among farms and ranches, the problem is more dramatic. Grizzlies descend along the stream bottoms, venturing 3 to 4 miles out into the valley. They often sleep by day in the secluded stringers of timber and thick brush, making nocturnal grazing forays into surrounding croplands. Attractive nuisances, such as old orchards, garbage dumps, or livestock carcasses, may draw them to farmsteads. A newcomer’s streamside home in the trees may turn out to be in the middle of a grizzly travel route. Some residents have been unnerved by the sight of a half dozen mammoth bears padding silently across a corral by moonlight or through a farmyard in the glow of a yard light.

Grizzlies have rarely killed livestock. More often, bears fall victim to landowners’ fears. Between 1976 and 1982, at least 13 Mission grizzlies were killed-a dramatic loss for an area that may have a stable population of only 25 bears. Reproduction may not cover. such losses, so managers are trying to intervene more rapidly to avert problems. In 1983, a large female and two cubs were trapped by tribal, state, and federal managers and moved to the Great Bear Wilderness after a farmer complained that they were feeding on a sheep carcass. The mother, dubbed Daisy, had been trapped before and had no history of mischief. It was not certain that she had killed the sheep. But managers now strive to relocate any bears that seem too familiar with humans or livestock. The strategy may be paying off. Since 1980, only four grizzlies have been killed, while six others have been trapped and relocated.

Despite relocation efforts, bears often return to their home ranges. They are capable of traveling great distances, even when slowed by less-agile cubs. Daisy and her cubs migrated 40 air miles down the eastern side of the Continental Divide, eventually settling in the heart of the Sun River Game Range. They have not approached human settlements since then. The episode was a loss for the Missions, but a productive female survived to bolster the future of a threatened species.

In the moment when a great bear bounds from the cage that has briefly contained her, in the spine-tingling seconds she spends summon ing her cubs and surveying her domain for a glimpse of her captors, there is an exhilaration that conveys both the darkest fears and the boundless joys that are the essence of the wilderness spirit. For the Salish and Kootenai people, still near in time to their wilderness roots, the Missions are a link with a heritage fast disappearing amid the frenzied press of civilization and change. For western culture, wilderness has become a place to rediscover the spirit of wildness and the richness and genetic diversity of the untamed world. The Missions are a meeting ground for both cultures, a place for them to rediscover their mutual roots in the unfettered earth that has shaped their destinies.

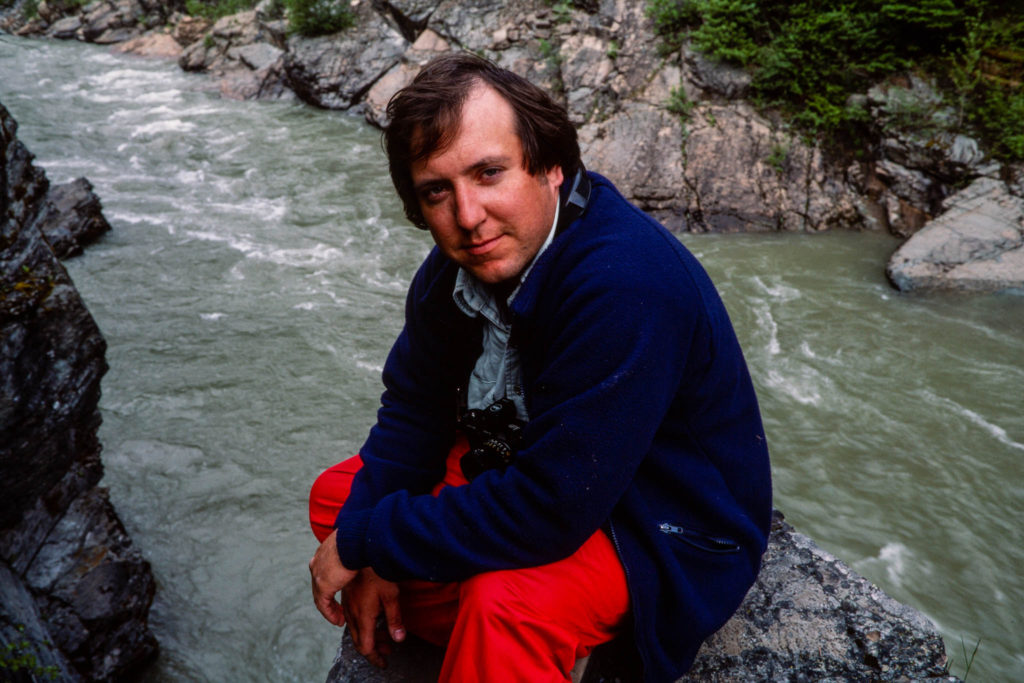

Don Schwennesen covered northwestern Montana regional news and outdoor issues through the 1990s for the Missoulian. He became editor and manager of the weekly Bigfork Eagle in 1998, after it was acquired by Lee Enterprises, the Missoulian’s parent company. He retired in 1999 and celebrated the end of the millennium on a six-month camping trek around Australia and New Zealand with his wife, Rose. Upon return, he joined as an active partner in his wife’s real estate business, re-starting a second career that began when he was first licensed in 1972. He continued to advocate for conservation and land-use planning, serving in leadership roles with Citizens for a Better Flathead, a local advocacy group. He and Rose also found time for travel, including annual extended backpack trips into Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. They celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2019, and they remain active in real estate, while supporting a variety of land-use and conservation causes. Their small orchard-vineyard still produces organic sweet cherries and grapes at the homestead overlooking Flathead Lake, and their passions range from travel, camping and wilderness hiking, to international folk dancing, geology/rockhounding — and of course grandchildren.

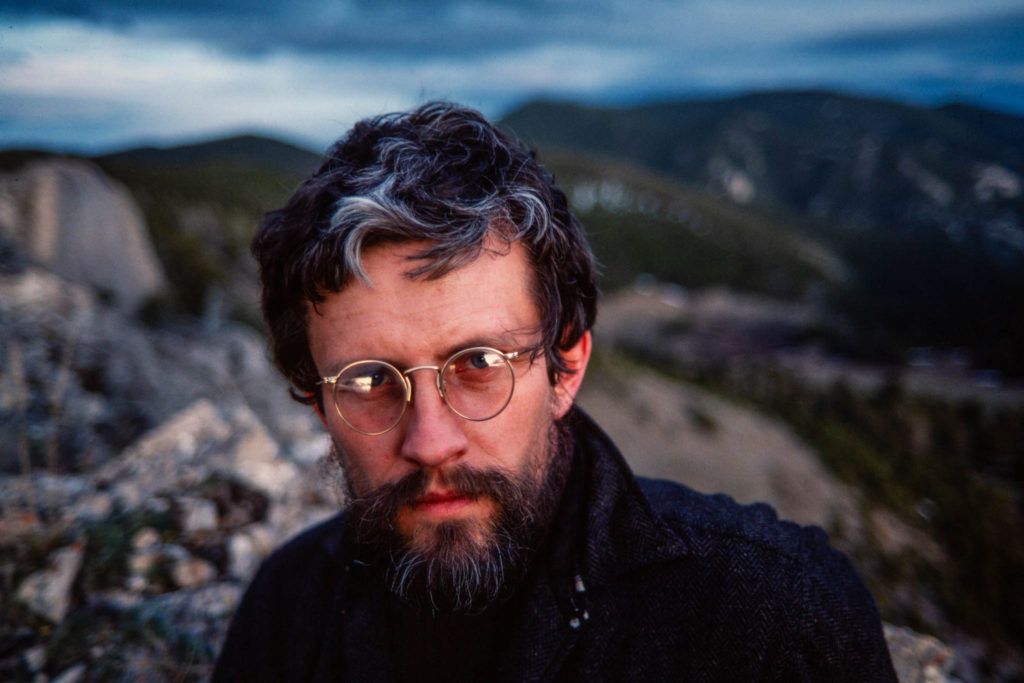

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.