By Steve Woodruff | Photographs by Carl Davaz

Glaciers sculpted the spectacular peaks of the Lee Metcalf Wilderness. Thundering rivers etched deep canyons in the land. But people, not nature, gave final form to this magnificent region of mountains and meadows. Like all wilderness areas, the Lee Metcalf is largely a product of politics, a place shaped through harsh conflicts and painful compromises.

The 259,000-acre wilderness, located southwest of Bozeman in the Gallatin and Beaverhead national forests, is a case study in the politics of preservation. Haggling men in three-piece suits decided in the distant halls of Congress what natural features to include in the wilderness. The area’s boundaries follow negotiated agreements, not the lay of the land. The area is even named for a politician, Montana’s late Democratic Sen. Lee Metcalf, an environmental champion who died in 1978.

Jagged 11,000-foot-high peaks of the Madison Range rise from the center of the Lee Metcalf. Fragile alpine basins, dozens of sparkling cirque lakes, and dense lodgepole pine forests surround such mountains as The Helmet, Sphinx Mountain, and Hilgard Peak. Clear streams tumble from the wilderness into the nearby Gallatin and Madison rivers, both nationally famous blue-ribbon trout streams. The Madison River cuts across the northernmost corner of the Lee Metcalf, raging 9 miles through the narrow, 1,500-foot-deep Beartrap Canyon.

The Lee Metcalf is a disjointed, four-part subdivision of what had been until 1983 the largest unprotected expanse of roadless country in the lower 48 states. The southernmost segment, surrounding the gently rounded Monument Mountains, adjoins the northwestern corner of Yellowstone National Park. The main body of the wilderness stretches northward, spanning the Taylor and Hilgard areas. The two northern most parcels encompass Beartrap Canyon, near the town of Norris, and the rugged Spanish Peaks, about 25 miles southwest of Bozeman.

Much of the area, especially the portion adjacent to Yellowstone Park, provides critically important habitat for a seriously threatened population of grizzly bears. The Lee Metcalf also supports herds of elk that migrate out of the park in winter, as well as year-round resident populations of elk, moose, and mountain goats. Bighorn sheep thrive in the remote alpine setting, and portions of the area are among the few places in the country where, under a quota system managed by the state Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, an unlimited number of sportsmen may hunt the wary sheep. Many of the wilderness lakes and streams contain native and stocked Yellowstone cutthroat trout, along with rainbow, eastern brook, and golden trout.

Spring, summer, and fall are brief interruptions in the long south central Montana winter. West Yellowstone, located a short distance from the Lee Metcalfs southern flank, typically sets record-low temper atures for the nation during the summer. The peaks of the Madison Range remain snowcapped most of the year, although much of the area is snow-free by mid-July. Wilderness trails vary in difficulty from gentle walks to technical mountain climbs, with elevations ranging from 6,000 to more than 11,000 feet. An increasing number of rafters and kayakers are discovering the Madison River in Beartrap Canyon, which contains some of the most challenging rapids in Montana.

The Lee Metcalf is unquestionably wild. But even for the wildest places, protection seldom comes easily. Wilderness designation is a fiercely competitive political process involving carefully planned campaigns, pressure tactics, and sensitive negotiations. More than anything, it takes time.

The Forest Service set aside portions of today’s Lee Metcalf as the Spanish Peaks Primitive Area in 1932. The agency placed a moratorium on development in the Hilgard Peak area in the 1950s, pending a decision on whether to classify it as wilderness, and the Bureau of Land Management later designated Beartrap Canyon a primitive area. With the passage of the Wilderness Act of 1964, speedy wilderness designation, at least for the northern end of the Madison Range, seemed almost certain.

But it took another two decades, several bills in Congress, a congressionally mandated wilderness study, and years of intense politi cal activity to forge the Lee Metcalf Wilderness.

Senator Metcalf tried several times to push a Spanish Peaks wilderness bill through Congress. His early efforts failed because of a sticky landownership problem involving Burlington Northern Incorporated. The railroad holding company owns much of the land in the Gallatin National Forest, its property intermingled in a checkerboard fashion with parcels of national forest.

In the early 1960s, Burlington Northern’s predecessor, the Northern Pacific Railway, decided to defer road-building and logging on most of its Madison Range holdings. Company officials had assumed that many of its lands were destined for quick wilderness classification and that the government would buy or trade for the land.

But more than a decade passed without much progress toward wilderness protection for the Madison Range. Meanwhile, an infestation of mountain pine beetles spread through the company’s timberlands, killing trees and lowering the value of the land. In 1975, the company asked to trade its 177,000 acres in the Gallatin National Forest for national forest land in western Montana, a deal that could have made wilderness designation for the Lee Metcalf relatively simple. But western Montana loggers, who viewed such a trade as a threat to their supply of public timber, went to Congress for help. Democratic Sen. John Melcher effectively blocked the exchange with a measure requiring congressional approval for any large land trade.

Senator Metcalf successfully sponsored a controversial bill in 1977 requiring the Forest Service to conduct special wilderness studies on several Montana areas, including the Taylor-Hilgard portion of the Madison Range. Despite the study, the area remained in legislative limbo. Finally, in 1978, Burlington Northern managers decided they had waited long enough for Montanans to contemplate the wilderness issue. The company announced plans to build roads across the national forest into its lands in the heart of the Madison Range.

“For 15 years we had sat on our hands,” says Don Nettleton of the Plum Creek Timber Company, Burlington Northern’s forest products subsidiary. “The status quo was no longer satisfactory.” The timber company was sincere in its plan to harvest timber from its land. But at the same time, Nettleton says, it was trying to make a point. “We were pushing the decision,” he says. “I’m convinced that there wouldn’t be a wilderness area there today if we hadn’t made an issue of it.”

The threat of roads galvanized Montana environmentalists. An informal group of Bozeman-area residents interested in protecting the mountains near their homes formed the Madison-Gallatin Alliance (MGA) in 1979. Some of the group’s early members had worked together on Montana’s 1978 anti-nuclear initiative; but for most mem bers, the push for the Lee Metcalf Wilderness was their first experience in the political arena.

Like any political campaign, protecting wilderness requires a solid organization. MGA relied on a hired organizer from the Montana Wilderness Association to get the group started. Much of the organizational work involved the important task of contacting landowners, businessmen, and other groups that might lend support to a wilderness proposal. During the next 3 years, MGA learned the hard way about the importance of having unity in a wilderness campaign.

Conservation groups in 1980 asked the state’s congressional delegation to designate a 550,000-acre wilderness extending from the Spanish Peaks to Yellowstone Park, covering portions of the Madison and Gallatin ranges. MGA produced attractive slide shows to win support from Montanans who never had and probably never would visit the wilderness. The group also sponsored marches and demonstrations to call attention to the threat of roads and logging in the pristine area. MGA’s leaders effectively used the media to spread information and gain support for the wilderness proposal.

Montana’s timber and mining industries staunchly opposed the proposal, as did snowmobile and off-road-vehicle enthusiasts. “We just didn’t feel that any more land should be locked up to motorized recreation or natural resource development,” says Gary Langley of the Montana Mining Association.

The task of settling the issue fell to the state’s two representatives and two senators. Because controversies over wilderness designation tend to be local in nature, Congress generally leaves such matters up to politicians from the affected state. Once the state’s delegation reaches a consensus, other members of Congress usually go along. With environ mentalists asking for more than one-half million acres and industry arguing for none, the delegation began pushing for compromise.

When MGA started making concessions, its organization threatened to disintegrate. Disagreements about boundaries and other issues began pulling apart the pro-wilderness coalition. MGA leaders found themselves at odds with the Montana Wilderness Association as well as with members of their own group. Various factions within the conservation community began lobbying the delegation for different versions of the Lee Metcalf bill. The wilderness advocates lost much of their political clout along with their unity.

“So many people were talking that nobody knew what the hell we stood for,” says past MGA President Dr. Richard Tenney.

By late 1982, after years of hearings, discussions, and behind-the scenes negotiations, the Montana delegation reached a hard-fought agreement on a Lee Metcalf bill. Senator Melcher was hurrying to get the bill approved in the final hours before the 97th Congress adjourned, when Republican Sen. Jesse Helms of North Carolina blocked the measure in retaliation for Melcher’s stance on an unrelated agriculture bill. The Lee Metcalf bill died when Congress adjourned without a chance to vote on the measure. The following year, after Melcher introduced another bill, triggering another series of debates and negotiations, the Lee Metcalf became a wilderness.

Politicians consider their wilderness legislation a notable success and a fitting tribute to Metcalf. “We preserved for the future this area as it is,” Melcher says. “And we could treat this land no better than that-to say, ‘No more change to it because what is here couldn’t be improved upon.’ “

But the price of such preservation is sometimes high, as Interior Secretary William P. Clark pointed out during a 1984 ceremony dedicating Beartrap Canyon, the nation’s first parcel of wilderness to be managed by the Bureau of Land Management. After making his first trip into a wilderness area, Clark told an audience gathered along the banks of the Madison River that “when we are designating a wilderness area, we have to be aware that we’re making a major trade-off.”

Although Clark was mostly bemoaning the loss of forests for logging and trails for motorcycle riding, his words were an appropriate commentary on the Lee Metcalf. Wilderness protection has become a contest where all sides lose something; nowhere is that clearer than in the Lee Metcalf. Burlington Northern’s Nettleton says his company lost financially because pine beetles wiped out much of its Madison Range timber during the long wait for the wilderness issue to be settled. Miners gave up the right to explore the rocky Madison Range for underground wealth, and motorcycle riders accepted another limit to their freedom. But the greatest trade-offs affect the land itself: portions of the Madison Range will be protected for future generations, while equally wild portions will be opened for development.

“It’s a disappointment, not a wilderness,” says Rick Meis of Bozeman, who helped lead the campaign for the Lee Metcalf. “It’s a wilderness compromise.”

The wilderness contains fewer than one-half the number of acres conservation groups originally proposed for protection in the Madison and Gallatin ranges. The two southern segments of the wilderness are divided by a wide snowmobile corridor, although special management restrictions there protect important wildlife habitat from development. The Jack Creek drainage, which would have formed a natural link between the northern and southern portions of the wilderness, was traded away to Burlington Northern in exchange for land elsewhere in the Madison Range. One of the greatest concessions made by environ mentalists was to exclude from the wilderness Cowboys Heaven, an area between Beartrap Canyon and the Spanish Peaks. With Cowboys Heaven, the Lee Metcalf would have contained dry canyon bottoms, high alpine peaks, and all the land forms in between.

Protecting the Lee Metcalf also exacted a toll on other Montana wilderness areas. The bill designating the area was packed with extraneous amendments, including provisions that opened short corridors for roads into the existing Absaroka-Beartooth and UL Bend wildernesses. Environmentalists’ efforts to persuade congressional committees to delete the provisions had little effect other than slowing the bill’s passage. Sections of the same bill dropped two roadless areas in eastern and northwestern Montana from consideration as future wilderness.

One environmental activist, outfitter Howie Wolke of Jackson, Wyoming, says the Lee Metcalf is a classic example of an area spoiled by politics. A founder of the radical environmental group Earth First!, Wolke faults wilderness advocates for making too many compromises. “They have moved away from confrontation and emotionalism and in a lot of cases have moved across that fine line between working within the system and being co-opted by the system,” he says.

Until the early 1970s, most conservation groups steered clear of politics. But in recent years, they have become active participants in the system. When they form a united front, environmentalists present a political force to be reckoned with. “We’ve demonstrated pretty clearly that there is a force out there,” says Carl Pope of the Sierra Club, one of the nation’s largest conservation groups. “It’s surprising how little it takes to make an impact because not that many people are politically active. Twenty or thirty people in a congressional district are significant. If you can get 100 people, you’re a power, a real power.”

Much of the political strength environmental groups wield stems from their ability to summon up an amazing amount of volunteer work from dedicated members. “If industry ever spent as much time on this as environmentalists, who do it out of absolute love for the land, there would never be any wilderness areas,” says Joan Montagne, MGA’s first president.

Wilderness advocates are still learning, sometimes painfully, how best to use their political muscle. In 1981, a number of Montana’s leading conservationists sent Senator Melcher a letter threatening to find an opponent to run against him unless he introduced a satisfactory bill for the Lee Metcalf Wilderness. Although the threat proved idle, close observers say the senator was so angered that environmentalists lost some of their ability to lobby him effectively.

Organizations opposed to wilderness also are becoming more proficient at politics. “We’ve had mixed luck with the political process in the past, but we’re learning how to utilize it better,” says Larry Blasing of the timber industry’s Inland Forest Resource Council in Missoula. Industry representatives usually talk of wilderness acres in terms of lost jobs and economic harm, words that carry considerable weight in political circles. “Factual economic realities have become a greater concern, and because of that, we’re probably having better luck in Congress,” Blasing says.

Although wilderness opponents seldom match environmentalists in manpower, they generally do a better job of providing their political candidates with financial support. “You need to support the kind of politician who supports your position, and it takes money to get those folks elected,” Blasing says. “That’sjust the way the system works.” The Sierra Club’s Pope says environmentalists are becoming more generous with their political contributions, but they need to donate more money. “Many individual members of Congress are responsive to money and not very responsive to grassroots pressure,” he says.

Money, power, and politics seem terribly out of place amid the natural beauty and serenity of the wilderness. Fortunately, wilderness politics is like a storm: no matter how hard it rages, it eventually blows over. Today, the protected portions of the Madison Range are a place of solitude where reflected peaks dance on rippled lakes and mountain goats bask in the late-summer sun. The clouds of controversy are at last lifting from the Lee Metcalf as environmentalists, loggers, and politi cians move on to other areas to wage new campaigns.

Steve Woodruff covered natural resources and the environment for the Missoulian through the mid-1980s, after which he served as the newspaper’s longtime editorial page editor. After stepping off from the newspaper in 2007, he continued writing about natural resources and worked as a strategic communications consultant for wildland- and wildlife-conservation organizations, and he taught journalism at the University of Montana. He also served as senior policy and communications manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Montana-based Northern Rockies and Pacific Regional Center, working on bison, bighorn sheep and grizzly bear restoration and a variety of public land-and-resource issues. Woodruff retired in 2017, lives in Missoula with his wife, Carol, and continues to explore Montana’s wilderness areas.

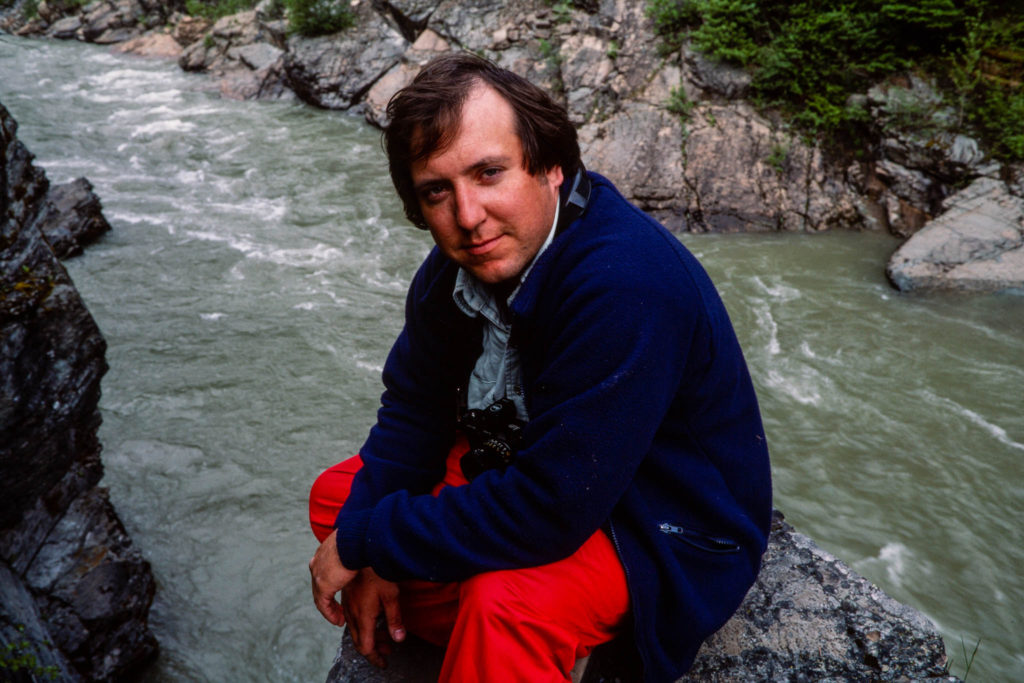

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.