By Don Schwennesen | Photographs by Carl Davaz

Where the northern end of the Big Belt Mountain Range shoulders toward the Rocky Mountain front, the Missouri River has carved a deep gorge through layers of sedimentary rock on the northeastern edge of the broad Helena Valley.

“Every object here wears a dark and gloomy aspect,” Meriwether Lewis wrote in July 1805 as the Lewis and Clark expedition made its way up the Missouri. “The river appears to have forced its way through this immense body of solid rock … and where it makes its exit below has thrown on either side vast columns of rocks mountains high.”

Lewis called it the Gates of the Rocky Mountains. Viewed from the summer tour boats that ply the gorge, the rocky columns seem to blend together, closing like gates until it is difficult to see where the broad river flows from the gorge.

High above the canyon, the 28,500-acre Gates of the Mountains Wilderness basks atop the northern end of the Big Belts as one of Montana’s smallest, least visited, yet most alluring wilderness areas. Wild canyons wind up through limestone formations weathered into spires, cliffs, twisting outcrops, and graceful, thin walls. Above the canyons, long timbered ridges wander among forested peaks, rocky outcrops, and gentle mountain meadows and solitary springs. Well-kept trails climb gradually into the wilderness through forests of ponderosa pine and Douglas fir, the open, parklike forest floor contrasting sharply with the dense undergrowth of many other wilderness forests.

Set aside as a primitive area in 1949, the Gates of the Mountains became a wilderness in 1964. Challenging, but nor formidable, the area is nearly ideal for a first trip into a wilderness. Yet it is lightly used,showing few impacts even at popular spots. Most visitors prefer to experience it as Lewis and Clark did, from the river far below.

In 1983, nearly 27,000 visitors cruised the river to ponder the limestone formations, watch mountain goats high on the canyon cliffs, and enjoy the wilderness vicariously from the tour boats operated by Gates of the Mountains Incorporated. Most of them probably had little ambition to hike up the steep canyons when the boat stopped at Meriwether Campground. They were content simply to know that a vestige of wild America had been preserved for future generations as habitat for wildlife and as a link with America’s frontier past.

Experts say that vicarious users are now the largest group of wilderness supporters, outnumbering those who actually visit the areas. Some have made a trip or hope to make one in the future, but most experience the wilderness through books, photographs, or stories told by friends. For them, it is not necessary to travel through the wilds to value them. Some suggest that in a world overrun by humans, perhaps there should be wilderness areas where people are not allowed at all.

In the Gates of the Mountains Wilderness, nature has imposed one severe limit that helps discourage visitors: except for brief periods in spring and fall, the land is arid. Spring comes early to the Gates, by Montana mountain standards. In a normal year, all but the highest forests are free of snow by mid-May. Porous, limestone soils quickly absorb the winter snowmelt, and the natural springs and streams of the wilderness come alive. The land greens as wildflowers blossom along the trails and spread across the high meadows. Among them is a rare member of the rose family, Kelseya uniflora, a striking heathlike shrub that clings to the limestone cliffs and stony summits in mounds and is found only in a few parts of Montana and Idaho on the Madison Limestone Formation. Pink blossoms of a tiny primrose, Douglasia Montana, also adorn the high ridges in great profusion. Another unusual flower, it grows only in Montana’s central mountains and parts of British Columbia and northern Wyoming.

By early July, streams disappear underground, and springs that flowed earlier become infrequent and unreliable. The canyons bake under the hot summer sun. For all but the most determined, the hiking season ends. The few hardy summer visitors must pack their own water at 8.3 pounds a gallon. Fall rains replenish the water and bring new life to the high springs, just in time for the hunting season. The Gates is a popular hunting area-too popular for many of the more experienced hunters-and it supports healthy numbers of elk, bighorn sheep, mountain goats, mule deer, and blue grouse. Black bear also inhabit the wilderness, as do bobcats and mountain lions.

Elk from the Big Belts gather in winter just north of the wilderness in the state’s 32,000-acre Beartooth Game Management Area, which also has a large resident elk herd. A grass-and-timber foothills region, it was a major cattle ranch until 1971. Bighorn sheep and mountain goats are also scattered across the northern end of the wilderness, from the Willow and Porcupine creek drainages to the steep hills and cliffs along the Missouri River canyon, where they are often visible from the river tour boats. Sheep also range over the upper slopes of Candle Mountain.

Sheep, goats, and elk were hunted to extinction in the Big Belts and many other places by the early 1900s, by a generation of hunters who naively viewed wildlife as an unlimited resource requiring no management or protection. State game managers began re-establishing the goats in the 1940s with surplus animals brought from the Bob Marshall Wilderness and its adjoining Deep Creek country. Elk from Yellowstone National Park were added in the 1950s, as were sheep from the Bob Marshall’s Sun River Canyon.

Bob Cooney, a retired state game manager long interested in the Gates, recounts how goats were trapped at a natural salt lick in the Bob Marshall, floated down a wilderness river in crates on 12-man rubber rafts, and then flown to Helena from a primitive airstrip for the final pickup truck ride to their new home. All survived.

Rocky limestone formations tum the wilderness canyons into mysterious miniature badlands whose side gulches and steep coulees invite exploration. Shadows of overhanging ledges and deep grottoes accent the escarpments and palisades, though no full-fledged caves have been discovered. Geologists say the strange formations were fashioned from stone originally deposited as marine sediments on the bed of an ancient warm, shallow sea. Similar deposits may be forming today beneath the Gulf of Mexico. Uplifted along with the Big Belts, the limestone zone was sculpted into intricate swirls and spires as erosion gradually carved the mountain stream courses. The gray limestones mingle with the tans and umbers of shale, especially near the rounded, timbered summit of 7,980-foot Moors Mountain, the highest point in the wilderness, and on the exposed flanks of nearby 7,443-foot Candle Mountain, where fossilized shells are embedded in the higher rocks. Visible from Helena, Candle Mountain was named a century ago when a forest fire burned to the top, causing the summit to glow for days like a distant candle. Gnarled, ghostly snags mingle with five-needled limber pines along Candle’s long ridge top, but most of the arid southern face still remains barren of trees.

Fires have left their mark on the dry forests in many parts of the Gates of the Mountains. On August 5, 1949, a disastrous forest fire turned into a human tragedy when afternoon winds whipped lightning caused flames into an inferno in Mann Gulch, just northeast of the wilderness. The blaze was intercepted by a recreation guard from Meriwether Campground and by 16 Forest Service smokejumpers, most of them fighting their first major fire. Turbulent canyon winds suddenly carried the fire down the gulch, cutting off their retreat. The men panicked and scattered when their foreman tried to start a “backfire” to create a burned island of safety ahead of the advancing flames. The foreman’s plan worked, and he survived, but only two others outran the flames in their final desperate race back up the punishingly steep canyon. The fire prompted a major investigation, and the memory of the tragedy lives on whenever Montana foresters recount the litany of the state’s great forest fires.

The wilderness climate-so vulnerable to fire and discouraging to summer visitors-creates a solitude that can draw interest from odd quarters. One wilderness manager relates how the Gates of the Mountains was recommended in a men’s magazine in the late 1970s in response to a reader’s inquiry about seldom-visited wilderness areas where discreet nude backpacking might be possible. The following season, an astonished trail crew reported meeting a couple who were hiking down the trail wearing nothing but shoes and backpacks.

Roadless lands south of the wilderness contribute to its isolation and make it effectively larger. A proposed 10,000-acre wilderness addition is expected to win early approval. It will move the southern boundary of the Gates to within a quarter-mile of the Beaver Creek Road to include Refrigerator Canyon, a natural wonder where cool winds blow even in summer beneath cliffs hundreds of feet high that narrow to a gunsight gorge scarcely 10 feet wide at the bottom. Still, the vast majority of visitors will probably continue to view the wilderness only from the Missouri River canyon, as they have since pioneer rancher Nicholas Hilger first began the river boat tours in 1890. Wild and alluring, the Gates of the Mountains represents wilderness at its finest, enjoyed by most from a distance and spared from heavy human impacts.

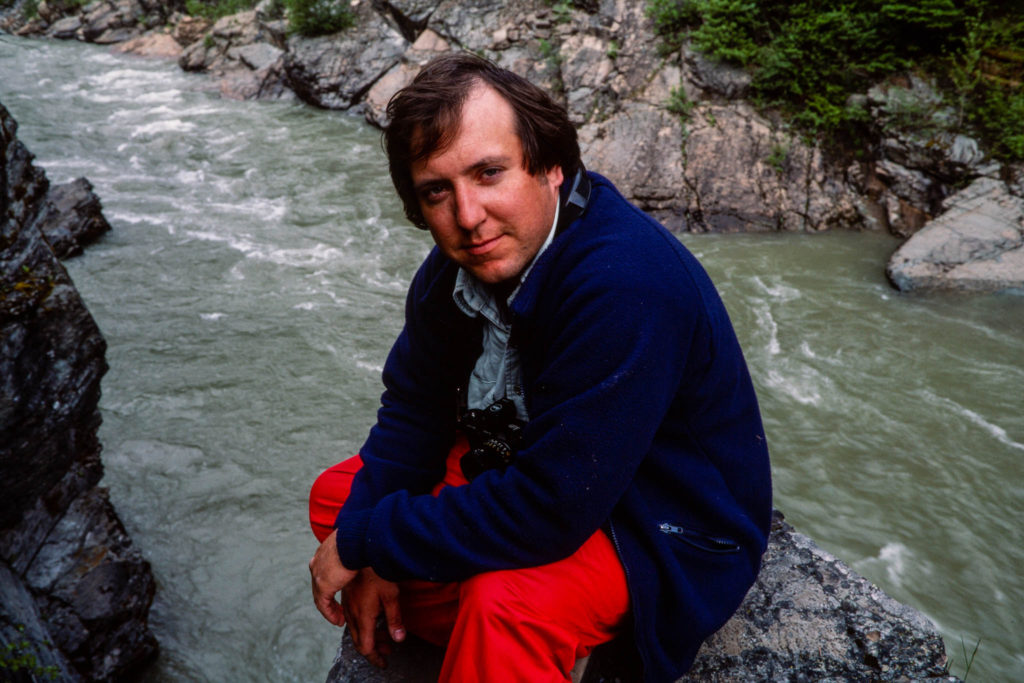

Don Schwennesen covered northwestern Montana regional news and outdoor issues through the 1990s for the Missoulian. He became editor and manager of the weekly Bigfork Eagle in 1998, after it was acquired by Lee Enterprises, the Missoulian’s parent company. He retired in 1999 and celebrated the end of the millennium on a six-month camping trek around Australia and New Zealand with his wife, Rose. Upon return, he joined as an active partner in his wife’s real estate business, re-starting a second career that began when he was first licensed in 1972. He continued to advocate for conservation and land-use planning, serving in leadership roles with Citizens for a Better Flathead, a local advocacy group. He and Rose also found time for travel, including annual extended backpack trips into Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. They celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2019, and they remain active in real estate, while supporting a variety of land-use and conservation causes. Their small orchard-vineyard still produces organic sweet cherries and grapes at the homestead overlooking Flathead Lake, and their passions range from travel, camping and wilderness hiking, to international folk dancing, geology/rockhounding — and of course grandchildren.

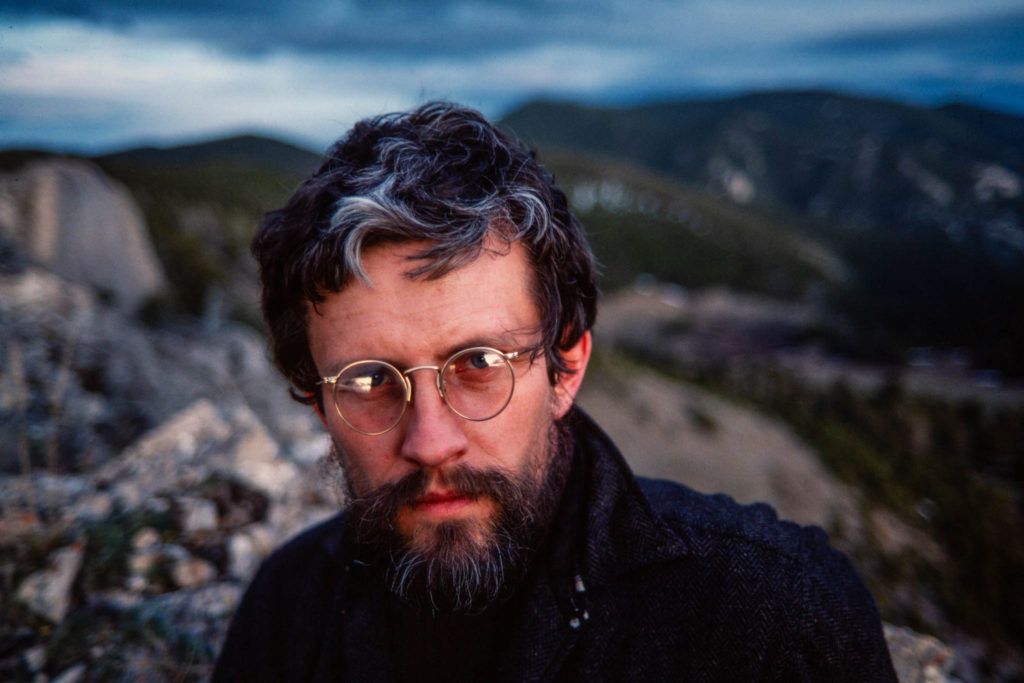

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.