By Don Schwennesen | Photographs by Carl Davaz

Solitude enriches the grandeur of the windswept ridges, alpine meadows, and forested valleys of the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness. At the 9,498-foot summit of West Pintler Peak, signs of humanity are as innocuous as the small brass marker that records where the U.S. Geological Survey measured the summit elevation. Yet the unseen hands of man affect the wilderness daily-managing its resources, changing the habits of visitors, and directing the ever-growing amount of recreation traffic in hopes of protecting the area’s wild qualities.

Wilderness is decried by some people as a lockup of valuable resources-areas set aside for the recreational pleasure of a few at the expense of all others. In reality, the land remains productive. Wilderness precludes only one of the five broad multiple uses of the national forests: commercial timber production. Other renewable resources-watershed, livestock forage, wildlife, and recreation-are the dominant ones in a wilderness area, and they, too, require management.

The phrase wilderness management may strike some as a contradiction in terms. In a place where man’s influence is supposed to be substantially unnoticeable, managing wilderness might seem unwar ranted. But in today’s world, wilderness is not always able to take care of itself.

“At the time a lot of these areas were set aside, public use was light,” says George Stankey of Missoula, a Forest Service researcher specializing in wilderness management. “The areas were remote, and many of the management tasks were taken care of by the remoteness. There just wasn’t the pressure.” But the situation has changed. Growing public use of wilderness areas has increased pressure in the past two decades, and every new visitor leaves some mark on the land.

The Wilderness Act directs agencies to preserve the wild qualities of the land as an enduring resource-a directive that requires federal land managers to take appropriate action to protect the wilderness. In most instances, however, “wilderness management” might be more accurate ly called “people management.”

Public attention usually focuses on the issue of wilderness designation, but many people believe that management of the areas is of equal or greater importance. “Getting lines drawn around an area is only part of the task,” Stankey says. “Unless we start seeing more and more attention on management, a lot of the energy devoted to wilderness allocation might be all for naught.”

The Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness illustrates many of the challenges facing contemporary wilderness managers. Located southwest of Butte, the wilderness straddles the Anaconda Range, a geological anomaly where the Continental Divide doubles back on itself in an east-west crescent nearly 80 miles long around the northern end of the Big Hole Valley. Along the western arm of the crescent, the earth has hurled up 10,000-foot peaks in a mountain range where the young granites of the Idaho and Boulder batholiths press against ancient Precambrian mudstones and gray limestones of the Madison Formation.

Named for pioneer Big Hole rancher Charles Ellsworth Pintler and for the historic copper-smelting town of Anaconda on its eastern end, the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness contains 159,086 acres extending more than 30 miles along the great Divide. It receives only moderate use. A rancher who lives nearby calls it Montana’s forgotten wilderness.

Like most wilderness mountain ranges, the rugged Anacondas form a geographical barrier that dictates human custom. Separating the sprawling ranches of the Big Hole from the Deer Lodge and Bitterroot valleys, the formidable terrain of the Anaconda Range has been a natural division for political jurisdictions and land management agencies. The boundaries of four counties and three national forests wander along the Divide and thread down the major ridges and drainages.

The wilderness is high country. With the exception of a few stream valleys, all of the land is above 7,000 feet in elevation and is locked in snow more than half the year. Mountain goats live in the area year-round, but the elk and deer that spend summers in the wilderness migrate to lower elevations in winter.

Historically, the area has been fringe territory, easily forgotten and left alone by managers who were preoccupied with the social demands of the settled valleys and with the timber and livestock forage that the more productive foothills can produce. The designation of wilderness areas within such rugged zones reflects the new public interest in those wild areas in this era when such places are fast disappearing.

That interest places new management demands on district rangers and forest supervisors, whose jobs are made more difficult when a wilderness is broken into different jurisdictions separated by great distances. Management of the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness is divided among the Deerlodge, Bitterroot, and Beaverhead national forests and five ranger districts, four of which play an active role.

The tasks associated with wilderness management are intended to protect the area’s wilderness qualities. Trails must be maintained or rebuilt periodically to allow reasonably easy access to hikers and horsemen while limiting damage to the surrounding land. Public education is becoming an increasingly important responsibility for managers. In popular areas, rangers check outfitter and visitor camps, often teaching people how to enjoy the wilderness without harming it. Seemingly small jobs, such as posting signs or revising maps, are essential in directing people away from problem areas.

Other management work is aimed more at wilderness resources than people. Grazing allotments and range conditions must be monitored, along with forest insects, diseases, and fires. Bridges and water diversions are sometimes necessary for reducing trail erosion. Historical sites and unusual plant and animal species must be safeguarded. As with most government activities, extensive record keeping is required for everything.

The work is guided by a management plan completed in 1977. The plan, drafted by rangers with advice from the public, lists 16 broad goals for protecting the wilderness. The goals range from maintaining natural diversity and populations of fish and wildlife to establishing consistent management practices throughout the wilderness. But with tight federal budgets limiting the amount of money for wilderness management, many of the goals have proved elusive.

During fiscal year 1984 in the Forest Service’s Northern Region, which includes more than 5 million acres of wilderness in five states, the agency spent about $1 million for wilderness management and $2 million for trail maintenance and reconstruction. Only a fraction of that money found its way to projects in the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness. In part, the expenditures reflect the general scarcity of federal money. But the budgets are also an indication of government priorities.

In the Forest Service, management of timber receives top priority, largely because timber sales produce revenue for the national treasury. Programs such as wilderness management and recreation receive less attention and funding because they contribute little money to federal coffers. In the Anaconda-Pintler, the four ranger districts that share responsibility for the area spent $41,479 or 1.6 percent of their combined budgets on wilderness management in 1984. Those same ranger districts spent $1.36 million — 54 percent of their budgets — on timber management during the same period.

Rangers are using better planning and cooperation among the widely scattered ranger districts as a positive step toward making the dwindling money stretch further. Managers meet twice a year to coordinate trail work and discuss problems. They also bring all the trail crews together once a year to pool their efforts on a major trail or bridge reconstruction job.

Cooperation also has helped along the Divide, where one of the more complete sections of the proposed Continental Divide Trail traverses the length of the wilderness. As the trail crosses and recrosses the Divide, it drifts in and out of different ranger districts. Use of the trail is starting to increase, and joint trail projects are improving sections where it is difficult to follow.

Wilderness management also involves other agencies, some of which play a crucial role. Fish and wildlife, for example, are under the state’s purview. Fishing is popular in the wilderness and draws heavy use around certain lakes. Many of the 42 fishable lakes in the Anaconda Range were once barren, but stocking since 1932 has populated them with rainbow and cutthroat trout. State stocking decisions can be a potent management tool for changing visitor habits. Fishermen are more likely to camp alongside a lake filled with trout than one that is barren. By stocking fish in one lake rather than another, managers are in effect redirecting people.

Sometimes, work necessary for sound wilderness management is conducted independently by naturalists whose motivation is scientific curiosity and a love for the wilds. For example, the Forest Service has done little to identify rare plants and plant communities in the wilderness. But Klaus Lackschewitz, retired assistant curator for the University of Montana Botany Department, spent 10 years studying the flowers of the Anaconda-Pintler Wilderness, cataloging hundreds of species. The wilderness plan calls for encouraging private research, but there is no guarantee that managers will learn of independent studies or put them to work. Without such studies, it is often difficult to watch for changes or protect critical sites.

To stretch budgets, rangers have turned to volunteer help. Students from as far away as Sweden have worked as wilderness guards or trail crew members. The trend, which extends beyond the Anaconda-Pintler, is starting to displace veteran seasonal workers. Concerned about both their job security and the quality of work done by volunteers, many wilderness rangers and trail crewmen have formed a Backcountry Workers’ Association to lobby for better wildland management and better opportunity for experienced workers.

With so much wilderness work still undone, some managers wonder whether their goals are too ambitious. Others believe that certain areas of heavy use are bound to become sacrifice areas, where wilderness pilgrims will exact a toll for leaving the rest of the wilderness alone.

Some management goals can probably be deferred in the Anacon da-Pintler, where use remains relatively light. But other long-range tasks, such as collecting baseline information on water quality and public use, will be crucial to rangers trying to watch for critical changes in the future. Paradoxically, the lure of wilderness adventure that leads to overuse and abuse of the land may also engender the public support necessary to bolster wilderness management. The skill of wilderness managers may well determine whether wilderness areas will endure as lasting examples of a world beyond the influence of man or linger briefly as the last islands to yield to the human tide.

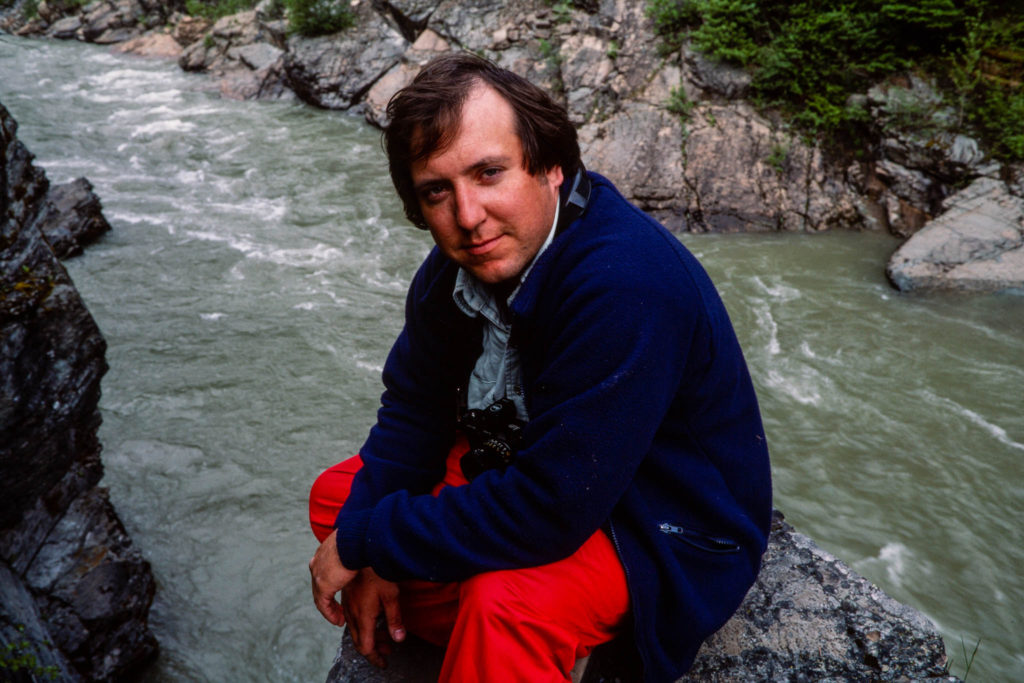

Don Schwennesen covered northwestern Montana regional news and outdoor issues through the 1990s for the Missoulian. He became editor and manager of the weekly Bigfork Eagle in 1998, after it was acquired by Lee Enterprises, the Missoulian’s parent company. He retired in 1999 and celebrated the end of the millennium on a six-month camping trek around Australia and New Zealand with his wife, Rose. Upon return, he joined as an active partner in his wife’s real estate business, re-starting a second career that began when he was first licensed in 1972. He continued to advocate for conservation and land-use planning, serving in leadership roles with Citizens for a Better Flathead, a local advocacy group. He and Rose also found time for travel, including annual extended backpack trips into Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. They celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2019, and they remain active in real estate, while supporting a variety of land-use and conservation causes. Their small orchard-vineyard still produces organic sweet cherries and grapes at the homestead overlooking Flathead Lake, and their passions range from travel, camping and wilderness hiking, to international folk dancing, geology/rockhounding — and of course grandchildren.

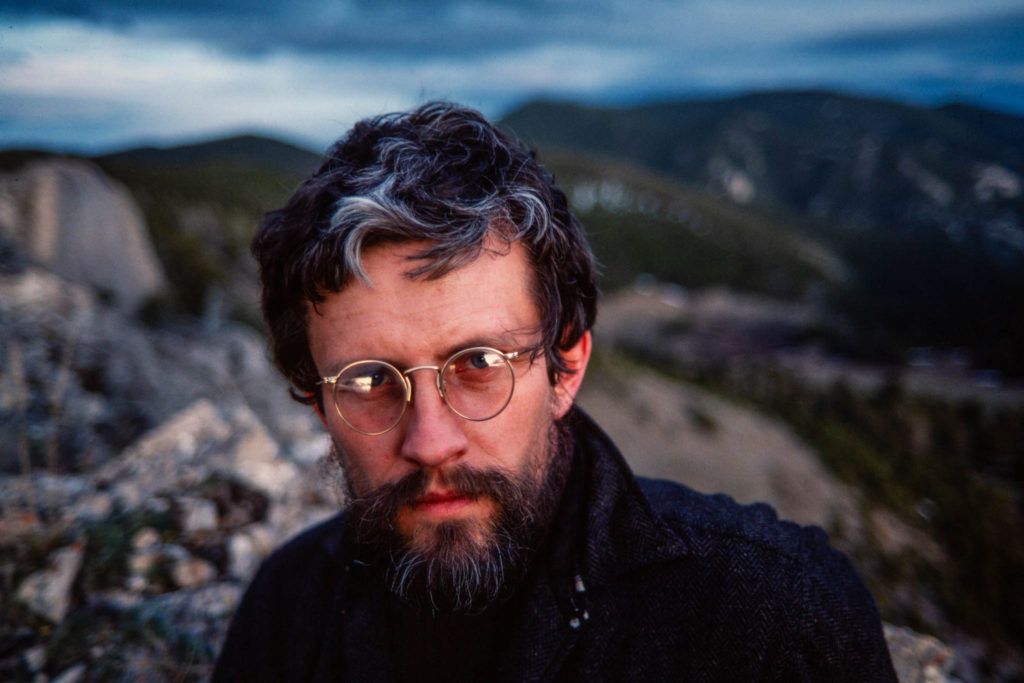

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.