By Steve Woodruff | Photographs by Carl Davaz

From the top of Montana, the wilderness seems boundless. Mountains stretch out in every direction, their peaks of jumbled granite cutting the horizon into a sawtoothed pattern of rock and snow. Flowing from the mountainsides are long plateaus, tundra-covered tables that run for miles before breaking into fields of boulders that spill steeply into distant valleys.

Here, in the heart of the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness, Granite Peak, Montana’s highest mountain, thrusts 12,799 feet into a cobalt blue sky. There is a vastness to this mountain, this place. But there are limits to the Absaroka-Beartooth, and they are steadily closing in. Even mighty Granite, the wildest of Montana mountains, is under pressure from the world outside.

The Absaroka-Beartooth, a sprawling, 920,400-acre wilderness in the Gallatin and Custer national forests between Billings and Yellowstone National Park, is a land of natural paradox. It is one of the most inaccessible and inhospitable places in the state. But it is also an area of captivating beauty.

In the Beartooth Mountains, on the eastern side of the wilderness, 28 peaks rise to 12,000 feet or higher. The mountains are described in part by their names: Tempest, Froze-to-Death, Thunder. The high altitude Beartooth plateaus form the largest single expanse of land above 10,000 feet in the United States. The Absaroka Range, in the western portion of the wilderness, contains less-rugged mountains-steep ridges flanked by grassy meadows and timbered canyons.

A harsh, subarctic climate dominates the wilderness. Winter, with its howling winds and heavy snows, comes and goes with little regard for the calendar. Temperatures can plummet 40 degrees Fahrenheit in a matter of hours. Summer is a fleeting season interrupted by almost daily thunderstorms that hammer the mountains and plateaus.

Yet the Absaroka-Beartooth has a beauty that is as subtle as tiny phlox blossoms clinging to a rocky ledge and as spectacular as a waterfall crashing hundreds of feet into a crystalline lake. This is a land of water. Glaciers and perennial snowfields feed more than 950 gemlike lakes almost all in the Beartooth Mountains-laced together by a network of rushing creeks and rivers. The entire wilderness is a watershed of unsurpassed quality for the Yellowstone River.

For all its harsh landscape, it is a fragile place where nature’s tenuous grip on rock and shallow soil is easily broken.

The Beartooths are built on a foundation of Precambrian gneisses and schists, believed to be some of the world’s oldest rocks. This foundation was covered by thousands of feet of Paleozoic and Mesozoic sedimentary rock, then uplifted nearly 70 million years ago by the same geologic forces that built the Rocky Mountains. Glaciers and weather scoured away the covering of sedimentary rocks, unearthing the flat, uplifted Precambrian foundation that forms today’s plateaus. The high mountain peaks are islands of sedimentary rock that survived eons of erosion. The Absarokas are made of softer sedimentary rock that weathered into gentler, more rounded mountains.

Glaciers still dot the rugged Absaroka-Beartooth, but they are small remnants of the icy shield that once capped the region. Other reminders of the distant icy past include rugged alpine cirques and deep, U-shaped valleys.

Elusive bands of bighorn sheep inhabit the plateaus, while mountain goats claim the alpine cliffs. Deer and elk summer in the wilderness, and many of the lower creek drainages have small populations of moose.

The wilderness is considered good habitat for the threatened grizzly bear, although its numbers are few. Black bears make their home here as well. Some people suspect that there may be an occasional Rocky Mountain wolf, an endangered species, but the evidence is limited to a few scattered tracks. Other wildlife includes wolverines, mountain lions, coyotes, bobcats, martens, marmots, and a host of small rodents. Birds include blue and ruffed grouse in the timbered canyons and bald and golden eagles in the skies above the plateaus and ridges.

About one-fourth of the lakes contain fish. Only a few waters, mostly in the Slough Creek Drainage, have native populations of trout; the rest have been stocked. Cutthroat and brook trout are the most common species, but rainbow and golden trout, arctic grayling, and whitefish are also present.

The Crow Indians cherished this region, sharing with it their name for their own tribe, Absaroka. They named the rugged mountains after fanglike Beartooth Mountain, on the southeastern edge of today’s wilderness.

Historians believe that ancient hunters began venturing into the Absaroka-Beartooth 9,000 years ago. Crow Indians climbed here to hunt the once-plentiful bighorn sheep. The U.S. Forest Service set aside portions of the region as the Beartooth and Absaroka primitive areas in 1932, and Congress named it a formal wilderness area in 1978.

The Absaroka-Beartooth has always been a place for man to visit, not to live. Through most of time, this wild land has remained inviolate.

But now humans, in their insatiable pursuit of pleasure and wealth, are increasingly encroaching on the wilderness. Many people equate wilderness designation by Congress with salvation of a natural area because the Wilderness Act prevents most kinds of development. But wilderness protection does not eliminate all threats to wild lands. As with many other wilderness areas throughout the nation, the outside world is leaning hard on the Absaroka-Beartooth.

The marks of man are clear throughout the Absaroka-Beartooth. Glacier and Mystic lakes are both dammed reservoirs. The Absarokas are still healing after decades of overgrazing by domestic sheep. And timber stands throughout the wilderness are growing decadent and vulnerable to pests and disease as a result of the overaggressive fire-suppression practices of the past.

The people who come here in search of climbable mountains, big trout, or simple solitude leave the most noticeable scars. The Absaroka-Beartooth has become a national playground, ranking as the fourth most-visited wilderness in America. All the visitors combined spent a total of 392,000 days in the Absaroka-Beartooth in 1983. Only the Boundary Waters Canoe Area in Minnesota, the John Muir Wilderness in California, and the Alpine Lakes Wilderness in Washington draw more visitors than the Absaroka-Beartooth. So many people come here each year that pollution from human waste has become an alarming problem.

Backpackers scrounging for firewood have created what foresters call a “human browse line” around many of the lakes. In alpine areas, a campfire can consume in minutes a tree that took centuries to grow. Several such fires by backcountry travelers can seriously disrupt a fragile natural system. Wherever man goes, he leaves his fire rings-blackened rocks circling a bed of charcoal-to mar otherwise pristine scenery.

Other problems include campsites denuded of vegetation and fragile soils compacted by informal trails through meadows. Caches of trash can be found in even the most remote corners, where supposedly only the most experienced and knowledgeable hikers go. Climbing to the top of Granite Peak, Forest Service rangers recently gathered and packed out sacks of soiled toilet paper. Even the first men to ascend the peak left their initials chiseled in the rocky summit.

Some wilderness visitors inflict plainly malicious damage, like carving initials on trees or discarding garbage on a lakeshore. But the most common vandalism can be attributed to simple carelessness, like that of a troop of hatchet-wielding Boy Scouts camped sloppily on the shores of Rainbow Lake.

Fishermen are among the worst offenders, leaving their Styrofoam bait containers everywhere and scattering fish entrails in the clear lakes, where the cold water slows decomposition. The most trampled and abused areas in the wilderness are around lakes containing fish.

Modern roads and trails make it easy for people to penetrate the Absaroka-Beartooth. Major roads provide access to the wilderness from the four compass points of Billings, Big Timber, Livingston, and Cooke City.

People living along the eastern approaches to the wilderness steer clear of Road 307 between Red Lodge and Roscoe on Friday nights because of the heavy traffic from Billings. If they drive their cars fast enough, people can leave work in Montana’s biggest city in the late afternoon and be in the wilderness before dark.

The Forest Service estimates that about 70 percent of the people who venture into the Absaroka-Beartooth live in nearby Montana cities. Located conveniently close to Yellowstone Park, the wilderness has also become a major attraction for out-of-state tourists. Articles in popular magazines have lured tourists by accurately billing the area as one of America’s premier wilderness areas.

Once they reach the wilderness boundary, visitors will find 32 major trailheads and more than 700 miles of maintained trails. But the rugged topography often concentrates recreation use in narrow corridors. Predictably, most of the backpackers congregate on weekends and holidays, within 10 miles of major trailheads. The most heavily used areas include the East and West Rosebud canyons and the popular Cooke City-to-Alpine trail. Thompson, Knox, and Rainbow lakes frequently support small cities of tents during the summer.

In the fall, hunters swarm into the Slough Creek, Hellroaring, West Boulder, and Buffalo Fork drainages. Wilderness rangers have found that few people stray farther than a quarter-mile off developed trails. For the relatively few hikers who do leave the trails, who sweat and struggle to reach the hundreds of isolated lakes and mountains that have no trails leading to them, the reward is solitude.

Concerned about damage caused by the growing number of people who visit the Absaroka-Beartooth, the Forest Service encourages wilderness users to treat the land with more respect. It has banned camping within 200 feet of lakes and 150 feet of streams.

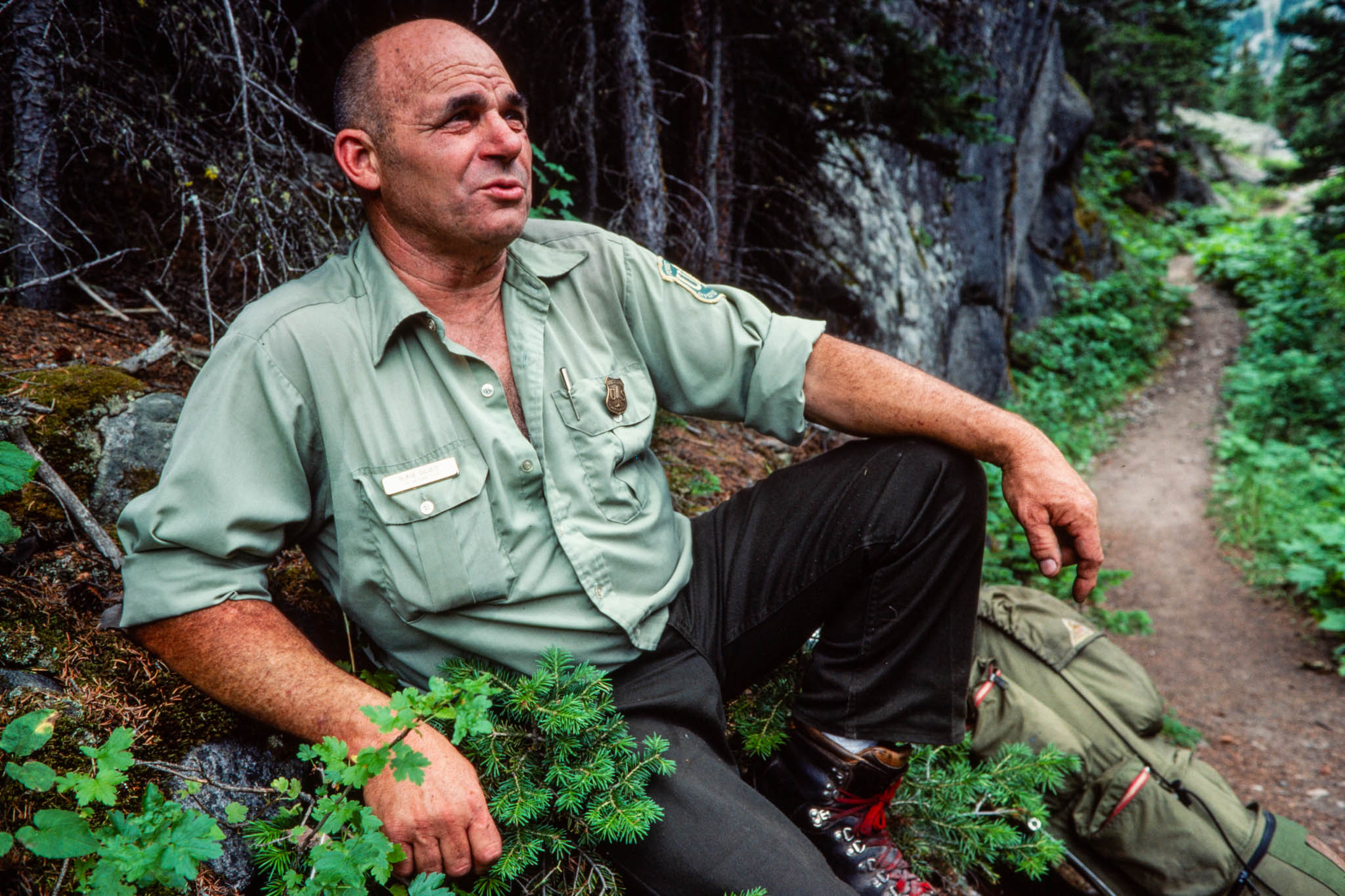

Wilderness rangers patrol the heavily used areas, enforcing regulations and preaching no-trace camping practices. They take the work seriously. “When someone hurts this place, it’s like they were hurting me,” says Blase DiLulo, a charismatic ranger who has spent a lifetime working in and around the Absaroka-Beartooth. The rangers are making progress toward protection, too. Wild strawberries and wildflowers are now struggling to take hold in campfire rings that were dug up and reclaimed a decade ago. Yet, as DiLulo says, “Everybody’s got to do their part, or we’re going to lose it.”

Recreationists are not the only threat to this great area. Modern-day prospectors equipped with bulldozers and drilling rigs are pressing their search for precious metals to the very fringes of the wilderness.

The boundaries of the Absaroka-Beartooth were drawn to avoid conflict over resources like minerals and timber. Most of the timber in the wilderness area is either too stunted or too remote to be considered worth logging. The area also seems largely devoid of minerals that interest miners, and the wilderness has little potential for producing oil or gas.

However, just across the Absaroka-Beartooth’s northern boundary is the Stillwater Complex, an amazingly rich belt of minerals running 26 miles between the Rosebud and Boulder rivers. The Stillwater Complex contains the largest chromite reserve in the United States, one of the nation’s largest reserves of nickel and copper, and a huge zone of platinum and palladium that is still being explored. The chromite is a high-iron ore that is imported to the United States for less than it would cost to mine it in Montana. And mining nickel and copper ores in the Stillwater Complex is unlikely soon because those ores are relatively low-grade.

But the platinum, a precious metal worth roughly the same as gold, is a different story. Mining claims for most of the complex are controlled by the Stillwater Mining Company, a consortium of the Anaconda Minerals Company, the Manville Corporation, and the Chevron Re sources Company. Although the consortium is still exploring its find, mining appears likely. The mining would take place outside the Absaroka-Beartooth boundary, but it could disturb life inside the wilderness through noise and air pollution.

Bill Cunningham of the Helena-based Montana Wilderness Association worries, too, that large mining operations could bring an influx of people to surrounding communities-people who could increase the human pressures on the Absaroka-Beartooth. ”There certainly is the potential for adverse impacts,” Cunningham says. ”It depends on how many people this brings.”

A 2-mile hike to Passage Falls, near Livingston on the western side of the area, offers a look at yet another threat facing all of America’s wilderness areas: political pressure.

When the Absaroka-Beartooth was established, it surrounded a 50-acre enclave of private land, an old homestead patented in the 1920s near the falls on Passage Creek. The homestead was recently subdivided into 33 parcels, and some of the owners want to build summer homes on their land. To do that, they need a road on which to haul building materials.

Wilderness laws do not restrict development of private land, but the landowners were prevented from building their cabins because the law forbids building roads across wilderness. Congress solved the problem in 1983 by redrawing the Absaroka-Beartooth boundary to take a 27-acre corridor near Passage Creek out of the wilderness. Work is proceeding on the road.

Although 27 acres is but a small fraction of the expansive Absaroka-Beartooth, the loss points to a weak spot in the wilderness-protection law: whatever Congress does, it can quickly undo.

Yet, like the unknown effect of nearby mining, political pressures remain mostly a potential threat. Recent efforts to open a snowmobile trail through the heart of the Absaroka-Beartooth, for example, did not get far. To date, wilderness has survived more major battles in Congress than it has lost. But who knows whether future generations of politicians will place as much value on an area like the Absaroka-Beartooth?

The potential exists for man to damage seriously, if not destroy, the wilderness qualities of this area. The people who come here to fish, hike, or probe the earth for riches may ultimately decide whether the potential becomes real. But for now, Granite Peak, the vast windswept plateaus, and the deep, dark canyons survive largely intact. Man and his activities have threatened, but not conquered, the wilderness. The Absaroka-Beartooth remains a bastion of wildness surrounded by a world of human pressures.

Steve Woodruff covered natural resources and the environment for the Missoulian through the mid-1980s, after which he served as the newspaper’s longtime editorial page editor. After stepping off from the newspaper in 2007, he continued writing about natural resources and worked as a strategic communications consultant for wildland- and wildlife-conservation organizations, and he taught journalism at the University of Montana. He also served as senior policy and communications manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Montana-based Northern Rockies and Pacific Regional Center, working on bison, bighorn sheep and grizzly bear restoration and a variety of public land-and-resource issues. Woodruff retired in 2017, lives in Missoula with his wife, Carol, and continues to explore Montana’s wilderness areas.

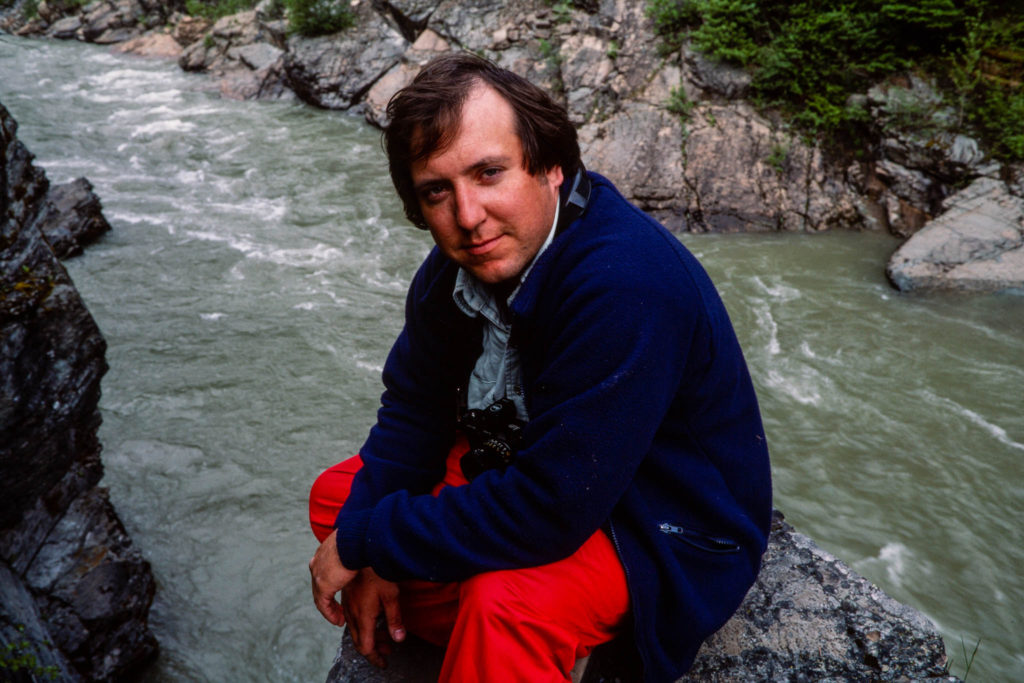

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.