By Don Schwennesen | Photographs by Carl Davaz

The high spur ridges of the Cabinet Mountains drop gracefully away from the rocky peaks, then plunge into the long, deep fault valleys that bound the mountains east and west. Viewed down the length of the range, they seem from some vantage points to form a line of arching buttresses separating glaciated valleys that open like the entrances to alcoves along a cloister. According to local tradition, early French trappers viewed the shouldered ridges, with their regular openings, and saw the semblance of a tier of “cabinets” or chambers.

The sequestered chambers of the Cabinet Mountains Wilderness hold an array of riches: diamond lakes, pearly cascades, emerald rain forests, and a king’s ransom in silver, copper, lead, and gold. The treasure rooms of the Cabinet Range were unlocked nearly a century ago, while Montana was still a frontier. Old mines border the wilderness, their names-the Snowshoe, the Gloria, the King, the Golden West, the Heidelberg-pages in local history. During the first two-thirds of this century, mines in and around the Cabinets produced more than 25,000 ounces of gold and 1 million ounces of silver. But as the surface veins gradually played out, the old miners were squeezed out, caught between the rock and the hard place of inflating production costs and a fixed federal gold price. Their labors unearthed but a fraction of the wealth beneath the Cabinets. Forgotten digs in the shadow of St. Paul Peak reveal that they passed over the blue-green outcrops of low-grade ore far up Rock Creek and Copper Gulch in the southwestern end of the range.

Today, a new generation of miners has returned to the Cabinets. Equipped with technology that can literally move mountains, they have discovered a thick seam of low-grade copper-silver ore that passes beneath the southwestern Cabinet peaks like a swath of frosting between the layers of a cake. Mining geologists traced the ore zone from similar deposits to the northwest, just across the narrow Bull Valley in the West Cabinet Range, where a new ASARCO Incorporated underground mine in Lincoln County is already the largest silver producer in the nation. Processing as much total ore every 2 months as Lincoln County produced in 6 decades, the new mine extracts more than 40 million pounds of copper and 4.2 million ounces of silver a year. Exploration geologists say the deposits beneath the Cabinet wilderness are even richer, yet they will scarcely put a dent in the voracious appetite of a technological world hungry for metals.

In a region where the timber industry has held sway, mining adds a new dimension both to the wilderness debate and the local economic balance. Where past battles have turned on whether to harvest and manage roadless timberlands, mining claims may affect timbered or alpine lands. Access can disrupt wildlife, and a discovery may mean rapid community growth and competition for local skilled workers.

The Cabinets are stormy mountains with an elusive past. The most westerly of Montana’s wilderness ranges, they are-at the 48th parallel the first tall rib of the Rockies to catch the Pacific storms from the Cascades, more than 200 miles to the west. Often shrouded in clouds, they receive up to 110 inches of precipitation annually, much of it as winter snow. The alpine snowpack piles to 10 feet or more, and a summer visitor may sometimes spot in a tree overhead an old trapper’s notch marking where a trap once rested on the crest of the winter snowpack. Huge old cedars, hemlocks, grand firs, and white pines cloak the lower valley bottoms. Tangled thickets of alder, mountain maple, and huckleberry climb the open sidehills and avalanche chutes.

The origin of the ore locked within the quartzite beneath the mountain is a mystery obscured by long ages in geologic time. The bowels of these mountains were formed as a seabed, beginning perhaps 1.5 billion years ago, as primordial continents still barren of life were abraded by rain and snow into fine sands and silts that in turn swept away down nameless rivers to settle into seas that have passed into eternity. For nearly I billion years the seabed thickened, and the deep layers fused into quartzite under the intense pressure and heat of molten rock injected from the earth’s core. Mineral veins followed by the early miners are evidence that plutonic forces infused the Cabinets with mineral lodes. But the deeper, low-grade deposits of strata-bound ore are more cryptic. At times the deeper strata may have lain beneath an arid basin in which inland seas periodically rose and evaporated. The receding seas may have concentrated dissolved minerals into rich brines that eventually became deposited in the quartzite layers known today as the Revett geological formation.

Thrust up along with the rest of the Rockies during the mountain building period that began roughly 70 million years ago, the Cabinets were scoured during the Ice Age by glacial icepacks nearly as thick as the range is high. Yet even the glaciated alpine valleys remain broken by stair step ledges, cliffs, and shelves that defied the age of ice.

The Cabinet Mountains Wilderness extends for 33 miles along the mountain crest, forming a 94,272-acre preserve that is generally from 4 to 7 miles wide. One of Montana’s first wild areas, it was set aside as a Forest Service primitive area in 1935 and officially classified wilderness with the passage of the 1964 Wilderness Act. In elevation the Cabinets are not a lofty range, but they rise from the lowest corner of the state, towering more than a mile above the surrounding valleys. Snow shoe Peak, in the midsection of the range is, at 8,712 feet, the highest summit. Mantled by Blackwell Glacier, it forms the backdrop for Leigh Lake, largest of the 85 lakes in the wilderness. Nearby 8,634-foot A Peak and 8,174-foot Bockman Peak are the only other mountains over 8,000 feet. The modest elevations belie the rugged splendor of the Cabinets. Sheer walls plunge more than 1,000 feet from crags such as St. Paul Peak, on the southern end of the range, and Snowshoe. About 25 spur trails climb the side valleys, typically ending at alpine lakes within 2 to 7 miles of the trailhead. A few lead to unmarked routes across the northern and central range, where steep scrambles ascend the tallest peaks. Hikers outnumber horsemen nine-to-one in the Cabinets. Livestock forage is scarce. With relatively short trails ending in rugged, alpine terrain, the Cabinets offer few opportunities for the extended saddle tours most horsemen prefer.

Fishing is a major attraction for wilderness visitors. Most of the lakes support native cutthroat trout, but some offer rainbow and brook trout, first introduced in the early 1900s. Many lakes were originally barren. In 1970, a visitor survey found that 65 percent of the people using the Cabinets were local residents, and 67 percent were on day trips. Nearly two-thirds of all visitors journeyed to just five lakes along the eastern side of the range. Leigh Lake accounted for 28 percent of the visits; Geiger, Granite, Cedar, and Sky lakes attracted another 36 percent. In the winter of 1981-1982, a snowslide felled trees for about 300 yards on the lower end of Leigh Lake. Kootenai National Forest managers, who had been pondering how to reduce human impacts at the lake, decided to accept nature’s solution to the problem and leave the windfall in place. “It kind of covered up a lot of the heavily used area,” says Gary Morgan, forest staff officer for recreation and minerals. “It isn’t all that easy to get to the lake anymore.”

Moose, elk, and white-tailed and mule deer summer in the Cabinets. Mountain goats inhabit the range year-round, and bighorn sheep introduced in 1969 are flourishing around Berray Mountain, on the western wilderness boundary. Mountain lions and black bears are abundant; in 1983, grizzly researchers trapped 40 black bears before finally capturing a grizzly. Sightings of the rare woodland caribou, a relative of the arctic caribou, were reported in the southern Cabinets as recently as 1962. Rare sightings and reports of tracks north of the Cabinets have persisted since then. But this most endangered of all North American ungulates slips inexorably toward extinction and may already be gone from Montana, representing a notable management failure. There are no plans to reverse the situation. Managers say the caribou’s large territorial needs make it difficult to protect. The animal also feeds largely on lichens in old-growth forests, a habit that puts it in direct conflict with timber production goals of liquidating old timber and raising younger trees.

The threatened grizzly bear may be headed for a similar fate in the Cabinets, but it is in the management spotlight today. Impacts of mining and other activities are often evaluated now in terms of the grizzly in areas such as the Cabinets where the great bear still survives. A creature with large territorial needs, the grizzly is a threatened species protected under the Endangered Species Act. Managers often run a gauntlet of public criticism as they search for ways to satisfy conflicting laws that encourage mining but also mandate grizzly protection.

A decade ago, grizzlies and mountain goats were the major hunting attractions in the Cabinets. Now probably no more than a dozen grizzlies are left. Sightings are rare. The lone grizzly captured and fitted with a radio collar in 1983 was a 28-year-old female believed to be the oldest documented free-ranging grizzly on record. The Cabinet grizzlies face twin pressures: mining under the southwestern flank of the wilderness and possible development of a major ski resort on the southeastern edge. Great Northern Mountain, south of Libby, is the proposed site for the resort that some local residents believe will bolster the area’s timber dependent economy. Old mining claims at the mountain’s base could become lodge and condominium sites. As development pressures close in on the southern Cabinets, wildlife managers struggle to understand the remnant grizzlies and their needs.

Few of the conflicts the managers face are as glaring as that between mining and wilderness. Many people are amazed that mining can occur within a wilderness. But the nine-year political battle leading to the 1964 Wilderness Act was a conflict that ended in compromise.

Miners had been given a free hand on public lands by the 1872 Mining Act. The spirit of the act was to promote mineral production for industrial growth. The act allowed prospectors to stake claims anywhere on the public domain and obtain outright ownership of their claims if they could prove the land would yield profitable minerals. Mining interests feared that wilderness legislation would diminish their favored status. They asserted, and still argue today, that minerals were the ultimate source of all material wealth. Many minerals were scarce, they added, and the nation did not have the luxury of ignoring important reserves within wild areas. Wilderness advocates, defending the genetic, scientific, and aesthetic wealth of wild lands, responded that most mineral deposits already had been found. Potential wilderness areas had been spared because they contained no significant minerals. Under the eventual compromise, wilderness boundaries were drawn to exclude known mineral deposits. Miners were granted 19 years to explore wilderness areas and stake new claims. They also gave up the right to obtain surface ownership of wilderness claims. The implication was that any mining scars in wilderness areas ultimately would be reclaimed.

The Cabinet wilderness boundary reflects the compromise. Along the southwestern edge, most of the Rock Creek drainage lies outside the wilderness due to the old, yet still active Heidelberg Mine. The excluded arm of land penetrates deep into the mountains, and the wilderness corridor shrinks to one-half mile in width. One primitive road serves the mine, and a second climbs to 6,000 feet on the western flank of Chicago Peak, where timber was harvested up to the wilderness boundary in steep clearcuts two decades ago.

In 1979, ASARCO began drilling exploratory holes near Milwaukee Pass, a short walk from the end of the Chicago Peak Road, to extract rock samples from potential copper-silver deposits hundreds of feet below. The mining firm also unveiled a 4-year plan to drill about 100 similar holes on as many 20-acre claims near Chicago Peak, St. Paul Peak, and Milwaukee Pass. Drilling equipment was shuttled to the drill sites by helicopter under the watchful eyes of Forest Service managers and conservationists worried about the future of the wilder ness. The 4-year drilling plan was reviewed by the Kootenai National Forest and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, the agency charged with protecting threatened species such as the grizzly. Ultimately the plan was approved with dozens of stipulations restricting helicopter flight pat terns, regulating use of drilling water from alpine lakes, limiting drilling seasons, and requiring special carpeting under motors and drill rigs to catch minor spills of fuel or lubricants. To provide extra living space for grizzlies disturbed by the drilling, Kootenai rangers closed four roads, canceled one timber sale, and postponed three others.

The plan was still challenged as inadequate by the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund, Defenders of Wildlife, and a local group known as the Western Sanders County Involved Citizens. But their lawsuit was dismissed, both a federal district court and an appeals court having concluded that the federal agencies had adequately protected the grizzly based on available information. Students from the University of Montana Wilderness Institute monitored the drilling work in 1980, and Forest Service monitors continued thereafter. In l981, the Forest Service expanded its grizzly work by reviewing the cumulative impact of all types of activity in and near the wilderness.

The study divided the Cabinets and surrounding forests into hypothetical bear habitat units, each covering about 100 square miles and containing sufficient habitat to support one female bear with cubs. The study projected that as many as 30 square miles of any unit could be temporarily disturbed without harming resident bears. But even that limit was pressed in 1982, when a second mining firm entered the Cabinet minerals race. U.S. Borax staked claims on both sides of ASARCO and unveiled drilling plans that would have cut one bear unit to 60 square miles. To accommodate both firms, the Forest Service closed more roads and required both firms to work in the same drainages at the same time.

At the end of 1983, time ran out for wilderness claim-staking. Plastic ribbons still flutter from trees marking the corners of the wilderness claims, but few traces of the drilling can be found. In 1984, while the Forest Service was still evaluating Cabinet mineral samples to judge their potential, ASARCO announced its corporate verdict. The firm unveiled plans for a major underground mine, one that will tunnel beneath the wilderness from a mile outside its boundary. Soon the Cabinets may test whether modern mining and wilderness can coexist.

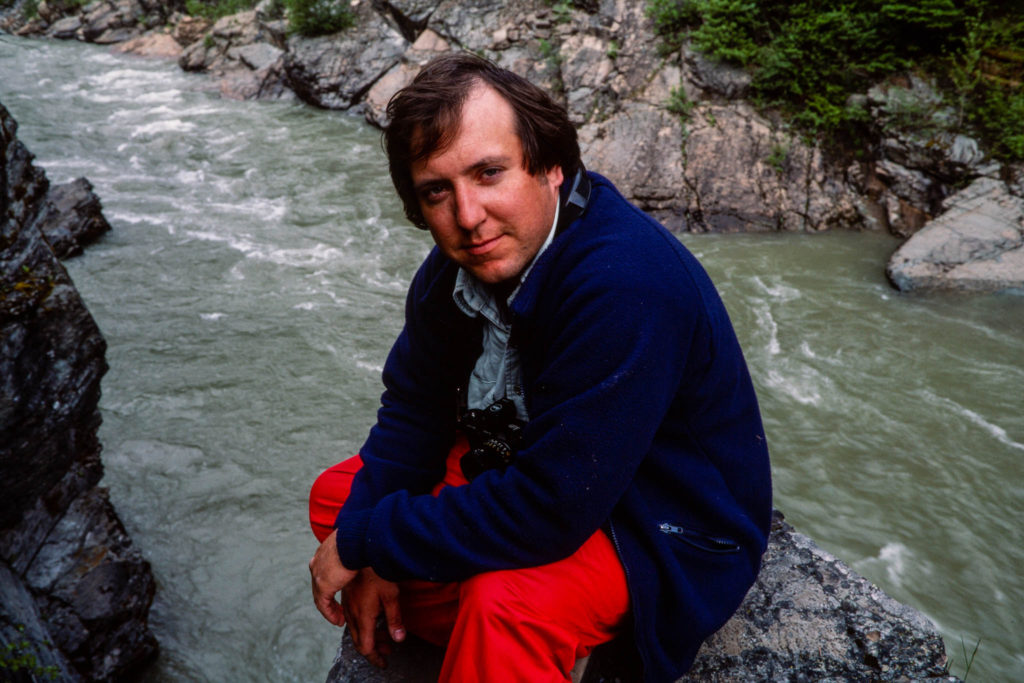

Don Schwennesen covered northwestern Montana regional news and outdoor issues through the 1990s for the Missoulian. He became editor and manager of the weekly Bigfork Eagle in 1998, after it was acquired by Lee Enterprises, the Missoulian’s parent company. He retired in 1999 and celebrated the end of the millennium on a six-month camping trek around Australia and New Zealand with his wife, Rose. Upon return, he joined as an active partner in his wife’s real estate business, re-starting a second career that began when he was first licensed in 1972. He continued to advocate for conservation and land-use planning, serving in leadership roles with Citizens for a Better Flathead, a local advocacy group. He and Rose also found time for travel, including annual extended backpack trips into Glacier National Park and the Bob Marshall Wilderness. They celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary in 2019, and they remain active in real estate, while supporting a variety of land-use and conservation causes. Their small orchard-vineyard still produces organic sweet cherries and grapes at the homestead overlooking Flathead Lake, and their passions range from travel, camping and wilderness hiking, to international folk dancing, geology/rockhounding — and of course grandchildren.

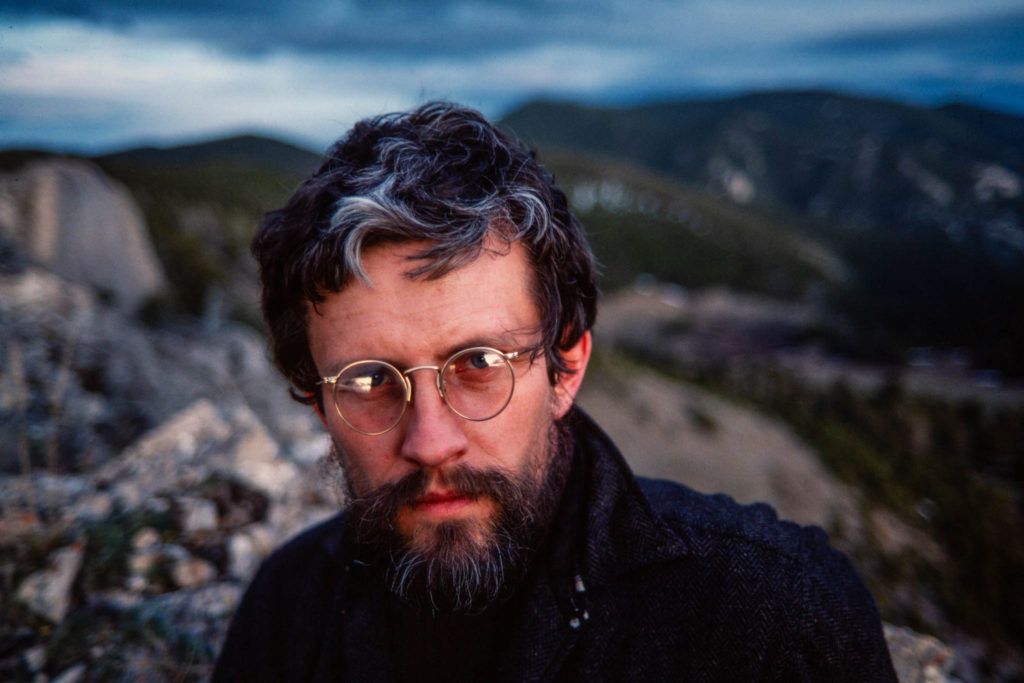

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.