By Steve Woodruff | Photographs by Carl Davaz

The lights of Missoula flicker in the distance when twilight settles over the Rattlesnake Wilderness. Neon signs twinkle, and car headlights weave like fireflies in the gathering darkness. The bright city contrasts sharply with the timbered ridges and rocky peaks of the Rattlesnake Mountains, where sunset casts a delicate pink glow. The only movement here is the wind, which gusts and swirls around deep cirques. After dawn, when the city fades into the haze of the valley below, daylight reveals more surprises: forests scarred by clearcut logging, glacial lakes held captive by earthen dams, and gravel roads that penetrate fragile alpine basins.

The 33,000-acre Rattlesnake is a wilderness perched on the brink of civilization. Wild, but not pristine, the area inspires one of. the most fundamental questions in wildland preservation: what constitutes wilderness?

The Rattlesnake’s winding ridges and secluded valleys rise from the backyard of Montana’s third-largest community. The area lies within walking distance of Missoula, and downtown pedestrians need only look beyond the rooftops to catch a glimpse of its mountain peaks.

No other wilderness area in the West lies so close to a sprawling city. Yet the Rattlesnake holds scattered pockets of remarkable wildness, hidden valleys tucked beyond the reach of all but the most adventurous hikers. Fewer than 1,000 people hike into the wilderness each year, a fraction of the number attracted to Montana’s better-known wilderness areas. Most Rattlesnake visitors head for the picturesque campsites and sometimes-good fishing at Twin, Farmers, and Little lakes. Relatively few hikers seek the lush basins and small valleys surrounding 8,620-foot McLeod Peak, a former vision-quest site for Salish Indians.

The Rattlesnake contains a collection of compact, lake-filled basins, each nestled between sheer headwalls and sloping forests. From the southern end of the wilderness, a knife-edged ridge arcs north past Stuart and Mosquito peaks, winding ever higher toward McLeod Peak, the tallest and northernmost mountain in the Rattlesnake. Bowl-like Grant Creek Basin hangs from the gentler timbered western slope of the ridge. To the east, the ridge top falls off sharply into high cliffs, cirques, and sparsely timbered basins. The area’s northern boundary joins the Flathead Indian Reservation only a short distance from the Mission Mountains Tribal Wilderness. The area immediately north of the Rattlesnake is a tribal sacred area closed to non-Indians. The Rattlesnake National Recreation Area, covering the lower elevations of the watershed, is a narrow natural buffer between the city and the southern boundary of the wilderness.

Grizzly bears, the living symbol of wild Montana, travel through the Rattlesnake’s upper reaches. The area forms the southernmost portion of the great bears’ range in the northern Rocky Mountain ecosystem, although the resident grizzly population is scarce, at best. The Rattlesnake also is home to bald eagles, goshawks, ptarmigan, arid nearly 100 other species of birds. Small groups of mountain goats still winter on the cliffs above Rattlesnake and Grant creeks, although their numbers have dwindled at the hands of hunters and poachers. Biologists are trying to restore goat populations by transplanting animals captured on the National Bison Range near Moiese. White-tailed and mule deer range throughout the forested areas along with a few elk. Many of the alpine lakes are stocked with rainbow, eastern brook, cutthroat, and Dolly Varden trout. Despite the area’s name, rattlesnakes keep to the lower elevations and have never been reported in the wilderness.

Rimming the U-shaped Rattlesnake Valley, the wilderness is the headwaters of Rattlesnake Creek and Missoula’s municipal watershed. More than 50 small creeks collect from springs, melting snowbanks, and clear lakes, bringing to Rattlesnake Creek water of uncommon purity. The parasite Giardia lamblia has infected portions of the creek close to town, but the wilderness waters remain clean and clear. The Rattlesnake’s importance as a watershed has long shielded it from the widespread logging, subdivision, and home-building that tamed similar nearby mountain valleys.

Although the area has few valuable minerals, it includes features of possible importance to geologists. Like most of Montana, the Rattlesnake was covered by glaciers during a series of ice ages that began nearly 60,000 years ago. Other glaciated areas of North America were largely reworked by each succeeding covering of ice, but the Rattlesnake was scoured by progressively smaller glaciers that left untouched, in the higher elevations, the geologic marks of past ages. The glaciers produced the Rattlesnake’s distinctive headwalls, cirque basins, and lateral moraines. The mountains here are built predominantly of quartzite, argillite, limestone, and siltite. The rocks that form the platelike base of the Rattlesnake were the bed of an ancient sea about 1.5 billion years ago. Geologists believe that the rocks formed perhaps 25 miles to the southwest, drifting over the eons to their present location.

On a map, the Rattlesnake boundaries are defined sharply. In the mountains themselves, the boundaries become less clear. Only Rattlesnake Creek and a few open fields separate the first one-half mile of the main access trail from scattered suburban homes. The trail is an old road that passes rusted wire fences, abandoned homesteads, and a concrete bridge before reaching the wilderness. Nearly 80 percent of the people who visit the Rattlesnake stay within 3 miles of the main trail head, never venturing beyond the national recreation area. Many people have no idea where the wilderness begins and ends.

Few Montanans questioned the need to preserve the Rattlesnake, but many fought over whether it qualifies as wilderness. Joe Mussulman, a University of Montana professor who works as a Forest Service ranger in the Rattlesnake, was among the skeptics. “It’s a wilderness legally but not environmentally,” he says. Mussulman knows the area as well as anyone, having explored it for nearly three decades. He led the initial public drive for protection of the Rattlesnake but fought against its wilderness designation. “Wilderness,” he says, “is something I know I’m in when I can’t find a trail.” Bob Marshall, the man who founded America’s wilderness-preservation movement one-half century ago, described wilderness similarly, calling it a place that “preserves as nearly as possible the primitive environment.”

Yet wilderness, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. “Some people, when they’re driving through on the interstate, perceive all of Montana to be a wilderness,” says Lance Olsen, a Montana psychologist active in wilderness issues. Other people contend that the only true wildernesses are the rock-and-ice summits of the highest mountains, an argument that seems to confuse the words primitive and pure.

Thurman Trosper, a retired forester and former president of the Wilderness Society, says the issue of wilderness purity is a smoke screen the Forest Service and others use to limit the size and number of wilderness areas. “If you have to pick an area that’s absolutely pure, then no area will qualify,” he says.

The Rattlesnake, for exam pie, is primitive but hardly pure. Portions of the area overlook a community of 65,000 people. Red lights blink incessantly atop television and radio transmission towers on nearby TV Mountain, and Boeing 727s roar over its ridges on their approach to Missoula’s Johnson-Bell Field. Inside the wilderness boundary, the area is marked by man’s handiwork. Humans made their first permanent intrusions in 1911, when workmen and mule teams began building rock-and-timber dams on eight of the Rattlesnake lakes.

The Montana Power Company, which once owned the city water system, bought and protected for decades more than 20,000 acres of the watershed as a means of guarding its investment in the water business. But in the 1950s, the company began logging its land. Loggers pushed a road deep into the area, reaching inside what would later become the wilderness boundary, to clearcut large tracts of the Lake Creek and Wrangle Creek drainages. Although the logging stopped, partly because of public criticism and partly because the best timber had been harvested, the roads remained.

As nearby Missoula grew, the area became a handy recreational retreat for city residents, who used the rough, narrow road along Rattlesnake Creek as the avenue of easiest access. The increasing number of people brought litter, gouged trails, and erosion.

Montana Power closed the Rattlesnake to cars and trucks in 1970 out of concern for water quality. But the area remained open to motorcycles, which could quickly carry fishermen to the popular alpine lakes. Because careless riders used their motorcycles to scramble to the most fragile corners of the area, damage to the land continued.

Many people who came here sought escape from the clamor of the city and were offended by the noisy machines. Public concern about damage from motorcycles broadened into general community interest in proper management of the Rattlesnake’s resources, and an organization called Friends of the Rattlesnake in 1971 began lobbying to protect the area. The group studied the many land-preservation statutes and strategies. Any number of laws might have worked, but only one, the federal Wilderness Act of 1964, would preserve the area’s wild qualities and assure the elimination of motorcycles.

Although touched by human activity, the Rattlesnake is an example of the kind of place Congress had in mind when it established the national system of wildland protection. Recognizing that wilderness takes many forms, Congress tossed aside the dictionary and wrote its own definition of wilderness. It described wilderness as “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by man, where man himself is a visitor who does not remain.”

Wilderness areas are places with recreational, scientific, educational, scenic, or historic importance. The Wilderness Act provides a marvelously elastic definition that recognizes simple ideals and complex realities. It uses words and phrases like untrammeled, primeval character, and natural condition but softens them with the words generally, primarily, and substantially.

Congress wields the act to protect a variety of areas for a variety of reasons. Wilderness can be a remote range of awe-inspiring peaks or a marshy nesting area for trumpeter swans. It might be a popular hiking area or a fragile ecosystem of scientific interest. America’s wilderness areas range from mountains in Alaska where few men have ever traveled, to small forested tracts in Missouri where nature is slowly reclaiming old garbage dumps.

Wilderness areas are managed to protect natural conditions. Motor vehicles are barred, logging is outlawed, and buildings and other permanent structures are prohibited. Mineral exploration was allowed until the end of 1983; now mining is allowed only on existing valid mineral claims. Hunting, fishing, camping, and other forms of primitive recreation are allowed but sometimes restricted to prevent damage to wilderness resources. The regulations protect only public lands, although in cases like the Rattlesnake, private parcels are sometimes included inside wilderness boundaries in hopes that government agencies might later buy or trade for the lands.

Business and industry groups fought against wilderness designation for the Rattlesnake, calling an area that includes roads, clearcuts, and dams a distortion of the wilderness concept. But Friends of the Rattlesnake President Cass Chinske says man’s imprint on nature should be viewed in proper perspective. “It all depends on the intensity,” Chinske says. “Those dams up there are not real high impact. They are not real ugly. This road is not ugly. I’ve been in Glacier National Park and walked up trails just the same size.”

Wilderness philosophers might never agree about what constitutes a truly wild area. In practice, the issue is a political one where wilderness becomes whatever Congress says it is.

For the Rattlesnake, wilderness may be a matter of law that eventually becomes a fact of nature. Man has undeniably touched this area. But, protected from development, the land now will be left to heal. Already, motorcycles have been banned from the wilderness and adjoining areas. The Forest Service is rapidly acquiring private lands inside the Rattlesnake so they, too, may be protected. Even in the Rattlesnake clearcuts, forests of rotting stumps are yielding to a new generation of trees, while the hard-packed roads are slowly disappearing beneath a carpet of weeds and wildflowers.

Steve Woodruff covered natural resources and the environment for the Missoulian through the mid-1980s, after which he served as the newspaper’s longtime editorial page editor. After stepping off from the newspaper in 2007, he continued writing about natural resources and worked as a strategic communications consultant for wildland- and wildlife-conservation organizations, and he taught journalism at the University of Montana. He also served as senior policy and communications manager for the National Wildlife Federation’s Montana-based Northern Rockies and Pacific Regional Center, working on bison, bighorn sheep and grizzly bear restoration and a variety of public land-and-resource issues. Woodruff retired in 2017, lives in Missoula with his wife, Carol, and continues to explore Montana’s wilderness areas.

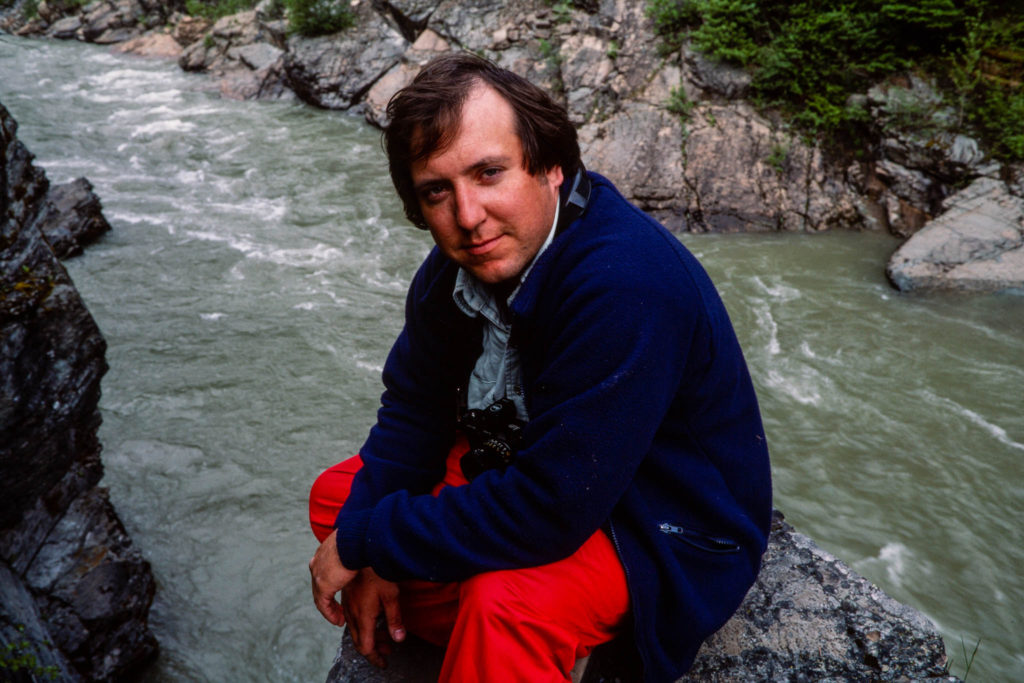

Carl Davaz became director of photography at the Missoulian in 1979, where 44,000 square miles of rugged western Montana made up the newspaper’s coverage area.

His partnership with reporters Steve Woodruff and Don Schwennesen underscored a commitment of words-and-pictures storytelling. Their newspaper project to explore elements of the often-contentious wilderness designation and management process became the book “Montana Widerness: Discovering the Heritage,” which Davaz photographed and designed.

In 1986, Davaz left Missoula for Eugene, Oregon, and The Register-Guard to become the family-owned newspaper’s director of graphics. Davaz and his Register-Guard staff were recognized as a 1999 Finalist for the Spot News Photography Pulitzer Prize for coverage of the Thurston High School shootings in 1998.

He retired in 2018 as deputy managing editor after working at The Register-Guard for 33 years. He remains active in photojournalism, publishing technology and book design. In 2022 he was honored by the Kansas Press Association as an inaugural member of the Kansas Photojournalism Hall of Fame.